Marquette University Marquette University

e-Publications@Marquette e-Publications@Marquette

Marketing Faculty Research and Publications Marketing, Department of

3-28-2022

In7uence of Social Media Posts on Service Performance In7uence of Social Media Posts on Service Performance

Carol L. Esmark Jones

University of Alabama

Stacie F. Waites

Marquette University

Jennifer Stevens

University of Toledo

Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/market_fac

Part of the Marketing Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Esmark Jones, Carol L.; Waites, Stacie F.; and Stevens, Jennifer, "In7uence of Social Media Posts on

Service Performance" (2022).

Marketing Faculty Research and Publications

. 302.

https://epublications.marquette.edu/market_fac/302

Marquette University

e-Publications@Marquette

Marketing Faculty Research and Publications/College of Business

Administration

This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION.

Access the published version via the link in the citation below.

Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 2 (2022): 283-296. DOI. This article is © Emerald Publishing

Ltd. and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e-Publications@Marquette. Emerald

Publishing Ltd. does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted

elsewhere without express permission from Emerald Publishing Ltd.

Influence of Social Media Posts on Service

Performance

Carol Esmark Jones

Department of Marketing, University of Alabama, the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama

Stacie Waites

Department of Marketing, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Jennifer Stevens

Department of Marketing and International Business, University of Toledo, Ohio

Abstract

Purpose

Much research regarding social media posts and relevancy has resulted in mixed findings. Furthermore,

the mediating role of relevancy has not previously been examined. This paper aims to examine the

correlating relationship between types of posts made by hotels and the resulting occupancy rates.

Then, the mediating role of relevancy is examined and ways that posts can increase/decrease

relevancy of the post to potential hotel users.

Design/methodology/approach

Within the context of the hotel industry, three studies were conducted – one including hotel

occupancy data from a corporate chain – to examine the impact of social media posts on relevancy and

intentions to stay at the hotel. Experimental studies were conducted to explain the results of the real-

world hotel data.

Findings

The findings show that relevancy is an important mediator in linking social media posts to service

performance. A locally (vs nationally) themed post can decrease both the relevancy of a post and the

viewer’s intentions to stay at a hotel. This relationship, however, can be weakened if a picture is

included with the post, as a visual may increase self-identification with a post.

Originality/value

These results have important theoretical and practical implications as social media managers attempt

to find the best ways to communicate to their customers and followers. Specifically, there are lower

and upper limits to how many times a hotel should be posting to social media. The data also show

many hotels post about local events, such as school fundraisers or a job fair, that can be harmful to

stay intentions, likely due to the irrelevant nature of local posts to customers who are likely to stay in a

hotel. National posts are seen as more relevant and likely to increase stay intentions, and the inclusion

of a picture can help local posts seem more relevant.

Keywords

Social media, Hospitality, Customer experience, Experimental design, Service strategy, Relevancy,

Social impact theory, Social identity theory, Service performance

Introduction

Businesses are increasingly using social media for marketing purposes; however, many are failing to do

so successfully. Over 90% of medium and large companies use social media marketing but cannot

accurately calculate the return on investment (Quesenberry, 2018). Additionally, over two-thirds of

companies are concerned about their ability to assess the success of their social media accounts

(Guttmann, 2019). One reason many companies are struggling to demonstrate social media’s impact is

their lack of a specific social media strategy. Many companies believe posting more frequently to social

media will increase performance since social media posting is often stated in popular press to directly

influence purchase intentions (Better Business Bureau, 2019). In this research, however, we highlight

how performance ultimately depends on the quality of social media posts, not quantity.

Quality of posts can refer to how viewers perceive the relevancy of the information (Carlson et al.,

2018). Social media should communicate relevant information about a company as it is more likely to

be shared. This might mean posting less often to deliver more valuable content (Quesenberry,

2018). Previous literature has confirmed the significance of post relevance in relation to perceptions of

quality (Carlson et al., 2018), engagement (Lee et al., 2020), privacy risk (Rehman et al.,

2020), information overload and social fatigue (Zhang et al., 2014).

While literature has established that relevancy is important, how to increase perceived relevancy is still

unclear. Many professional tips for what to post to social media suggest posts be relevant (Barnhart,

2020; Quesenberry, 2018) but do not offer guidelines on how to ensure the content is relevant to

users. Current research also has contradictory findings in offering suggestions of how often to post,

further increasing the need for social media guidelines in services marketing. Some studies have

suggested that less than once a day is best (Mariani et al., 2016), while other studies have suggested

posting four times a day (Mariani et al., 2018).

Therefore, this paper addresses these gaps by using social impact theory in a hotel service context,

which produces several unique managerial contributions. First, this research examines the number of

social media posts and actual hotel occupancy to show how often a company should post to see the

best behavioral results. Second, this research explores the content of actual social media posts to show

which content categories that are typically posted (e.g. restaurant menu versus general holiday posts)

are most effective in increasing hotel occupancy. These first two managerial contributions clarify

previous contradictory findings on how often to post and what general topics garner more hotel stays

and contribute clear directions for social media managers in service contexts. Next, we are among the

first to provide guidelines on how to increase relevancy of social media posts through national content

and picture inclusion.

From a theoretical perspective, the results contribute to social impact theory by illustrating that a

company’s social media posts can have social influence over an individual’s consumption behavior (i.e.

hotel stays). Social impact theory states that too many targets of influence can diminish strength

influence from one source (Latané, 1981). However, the findings presented here show that too much

information from one source can also dilute influence. For hotel social media, too much posting can

spread influence too thin and lead to a drop in performance. Additionally, while social impact theory

recognizes source strength, immediacy and number of sources as factors in creating influence, our

research shows that social influence is more impactful when it is relevant to the influenced party.

Relevancy of information is an important theoretical contribution to social impact theory’s tenet of

influence strength; this provides an important foundation for future work to further examine relevancy

as principle of social impact theory. The findings presented suggest practical ways social media

managers can increase relevancy through post content and how often to post to optimally influence

users. Overall, the results of this paper provide a foundation for service marketers to develop more

successful social media strategies.

Conceptual development and hypotheses

Social media and service performance

Research considering firm- and consumer-generated content has shown that social media can

influence how consumers respond to firms (Hutter et al., 2013; Gurrieri and Drenten, 2019). Hennig-

Thurau et al. (2015) examined the “Twitter effect,” which suggests microblogging word of mouth

(MWOM) shared through Twitter positively impacts early product adoption by immediately

disseminating consumers’ post-purchase quality evaluations. Social media activities have been shown

to positively impact consumer willingness to pay a premium price (Torres et al., 2018) and retail sales

(Kumar et al., 2016). Although social media posts are often unidirectional communication, the

frequency of messages can reduce uncertainty and increase credibility (Berger and Calabrese,

1975; Ledbetter and Redd, 2016).

Research on hotel-specific social media has examined how motivation and opportunity increase a

user’s involvement with hotel social media that will increase their likelihood to revisit the page (Leung

and Bai, 2013). Research has also examined the positive prediction of hotel performance ratings and

the impact of responses to negative comments (Kim et al., 2015), as well as similar effectiveness across

platforms (Leung et al., 2015). Research indicates that satisfaction with a hotel’s social media presence

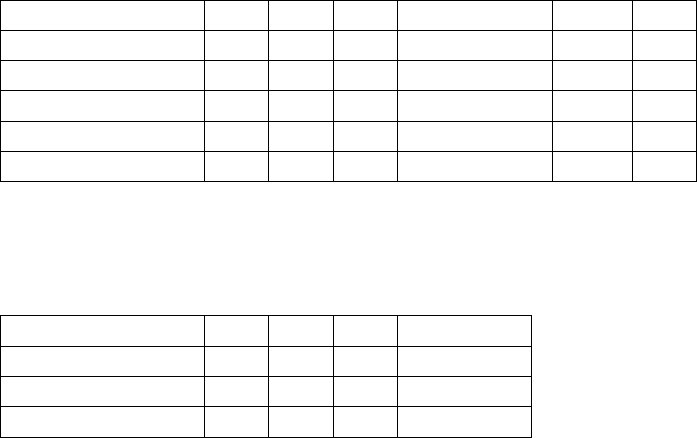

positively influences intentions to stay at the hotel (Choi et al., 2016). See Table 1 for a literature

review regarding how social media has been investigated within service contexts.

Social impact, social identity theories and relevancy

Research on social media strategy emphasizes the importance of frequent postings to maintain

engagement from consumers (Ashley and Tuten, 2015). However, researchers have yet to find a clear

answer regarding how often a company should post on social media. Some research suggests that

engagement is strongest for the initial post, while the impact of subsequent posts negatively impacts

engagement (Mariani et al., 2016) before beginning to increase again around four posts (Mariani et al.,

2018). These findings indicate the relationship between post frequency and consumer response is non-

linear. Social impact theory provides an explanation for this non-linear relationship.

Social impact theory (Latané, 1981) has been used to explain social media usage by firms (Torres et al.,

2018; Perez-Vega et al., 2016). This theory is uniquely suited to explain consumer responses to social

media via the effect of social influences on changes in consumers’ behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes

(Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004). A social influence is a direct or indirect influence at the interpersonal,

group or socio-cultural level and involves effects that can impact consumers’ thoughts, judgments and

behaviors (Turner, 1991). Thus, social media posts from a company (such as a hotel) represent a type

of social influence that impacts consumers’ behaviors and attitudes. Social impact theory states that

the difference in influence from 0 sources to 1 source is greater than the difference between 1 and 2

sources. Moreover, the number of targets changes the impact. The more targets receiving social

influence, the less any one target feels the influence (Latané, 1981; Esmark Jones et al., 2018). Recent

research has found that the more often educational institutions post, the less users engage with each

post (Peruta and Shields, 2017). The same could hold for other effects in that a threshold exists

wherein too much posting dilutes influence and reduces behavioral outcomes.

Traditionally, social influences are perceived in linear terms, whereby the frequency of social influence

directly diminishes or enhances behavior. As social impact theory outlines, we suggest that social

influence (social media posts) will impact behavior (hotel stays). However, the impact of such social

influences need not be linear, suggesting the presence of threshold effects (Stacy et al., 1992). Some

research has found that after an initial social influence, the impact of each additional social influence

declines before eventually beginning to accelerate again and vice versa (e.g. U-shaped and inverted-U

trending; Stacy et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 2014). In terms of social media posting for hotels, we predict

that the first post will be the most influential as it initiates awareness; the first post should generate

more hotel stays than the second post. However, as social media posts accumulate, the

inconsequential amounts of influence will continue to combine, crossing a threshold of significance to

again make the posts impactful on behavior.

H1. The relationship between post frequency and hotel stays is non-linear: after a certain number of

posts, hotel stays decrease to a minimum, at which point the relationship between posts and

stays becomes positive again.

The content of the posts must also be relevant to the audience for it to be effective (Ellis-Chadwick and

Doherty, 2012; Henninger et al., 2017). Relevancy has been shown to aid in higher evaluations of a

brand’s message (Chang, 2018) and advertising (Campbell and Wright, 2008). Relevant ads get more

attention (Jung, 2017) and increase the likelihood viewers will accept the advertising message (Zeng et

al., 2009). Research on relevancy typically looks at how the message is relevant to the brand (De

Keyzer et al., 2021), website or task (Resnick and Albert, 2016). Less research has focused on how the

personal relevancy of social media communications could impact behavior.

Social impact theory suggests immediacy impacts influence. The closer an influence is (either physically

or psychologically), the greater the influence (Latané, 1981). According to this tenet of social impact

theory, a social media post that is specific to a locale that the viewer is not in could decrease

immediacy and influence (hotel stays). Influence is also stronger when coming from a person’s group

(Latané, 1981) and local posts limit the number of people who would be considered in-group.

Combined with social identity theory, we propose that this reduction in influence from posting about a

local event can be explained by decreased relevancy to the viewer. Social identity theory (Tajfel,

1979) suggests that people act according to their identity, explaining how similar others (in-group)

tend to be looked upon more favorably than dissimilar others (out-group). Considering research on in-

group and out-group messaging evaluation, information associated with one’s in-group is typically

positively evaluated, while out-group information is discounted (Leach and Liu, 1998).

In the context of social media posts and hotel stays, viewers of a post will likely see posts aimed at the

local community as “them” (out-group) posts and nationally directed posts as “us” (in-group) posts.

Because an object or activity (i.e. social media post) is personally relevant when it is perceived to be

self-related or influential in motivating or achieving personal goals (i.e. choosing a hotel; Broderick,

2007; Xia and Bechwati, 2008), in-group posts should be more relevant to the customer (Huang,

2006; Carlson et al., 2016). Thus, posts about national events will be relevant as more individuals

associate national posts with their in-group compared to posts about local events, which are

associated with the hotel user’s out-group.

H2. A social media post about a local event will be perceived as less relevant than a post about a

national event.

We expect relevancy to be positively related with intentions to stay at a hotel. Social identity theory

suggests that individuals will act in ways consistent with their identity and group (Tajfel, 1979), such as

increased likelihood to stay in a hotel that posts relevant information. Research on relevancy confirms

its role in cognitive, affective and behavioral responses (Howard and Kerin, 2004). Perceptions of

message relevancy can increase persuasion (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986), attention to advertisements

(Jung, 2017), favorable attitudes (Trampe et al., 2010) and influence intentions to purchase (Alalwan,

2018). Research using social identity theory has shown the use of certain social media features

depends on interaction with relevant groups (Pan et al., 2017). Therefore, we predict that perceptions

of relevancy will positively impact intentions to stay at a hotel.

H3. Relevancy will have a positive relationship with intentions to stay at a hotel.

Social identity posits that identity salience will increase the likelihood of behaving in accordance with

one’s identity. Research has shown that images on social media can help create an identity (Lindahl

and Öhlund, 2013), increase engagement (Peruta and Shields, 2017), increase perceptions of social

presence, decrease loneliness and offer increased intimacy by better simulating real-life interactions

(Pittman and Reich, 2016). When compared to text only, text combined with an image increases the

impact of a product’s message (Yoon, 2018). Further, images are trusted more than text due to their

perception of being more “real.” The viewer of an image is therefore more likely to feel the same

emotions as the poster felt and intended (Pittman and Reich, 2016), increasing the relevancy and

influence of the post to the viewer. Adding a visual may make an identity more salient by increasing

the probability that the viewer will identify with the post and lessen the negative impact of a local post

on relevancy.

H4. Including an image will moderate the relationship between post type and relevancy such that the

negative relationship between a local post and relevancy will be weakened when a picture

accompanies the post.

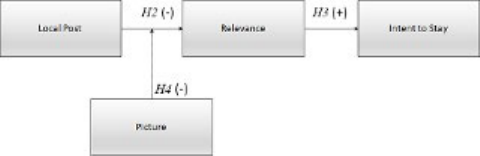

Methods

The conceptual framework is presented in Figure 1. To test the hypotheses, three studies were

conducted. The first study uses actual social media posts and hotel occupancy to determine the

optimal number of times a company should post to social media. This study also examines the content

of posts to determine what types of topics have the most beneficial impact on hotel occupancy rates.

An experiment is used for the second study showing the impact of a locally versus nationally themed

post on hotel stay intentions as explained through the relevancy of the post. Lastly, a third study shows

the moderating influence of a visual included in a post.

As social media metrics may be context-specific and differ by industry, a small pilot study was

conducted using secondary data. Data were gathered from a 12-year period (2008–2019) that included

annual rates of US adult social media users (Clement, 2020; Perrin, 2020) and the average US hotel

RevPAR (revenue per available room = average daily room rate x occupancy rate; Lock, 2020). The

results show a strong and significant correlation (r = 0.96, p < 0.001) between social media use and

hotel RevPAR. The results highlight the importance of understanding how social media and RevPAR

operate together.

Study 1 A: number of posts per week and occupancy

Procedure.

Study 1a tests H1, examining the relationship between the frequency of social media posts and hotel

stays. Data were obtained containing average occupancy (average number of rooms filled out of 100

per night for the week) rates over two one-week periods (April 8–14, 2018 and June 17–23, 2018) for

44 hotels in the eastern USA, all owned by the same parent company. The hotels consisted of multiple

hotel brands ranging from 71 to 343 rooms (M = 128) and an average daily rate of approximately $75–

325 (M= $140). Additional data were then collected for each hotel about their social media presence,

including the average number of tweets per week (total number of tweets divided by the number of

weeks since the hotel joined Twitter), the average number of Instagram posts per week (total number

of Instagram posts divided by the number of weeks since the hotel joined Instagram) and the average

number of Facebook posts (average number of posts per week for the four weeks of March 10 to April

7, 2018 and the four weeks of May 20 to June 16, 2018; Facebook does not have an exact user start

date or total number of posts feature). The three averages for each social media platform were then

combined to obtain a total average of how often each hotel posts per week. An average occupancy

score was created for the two weeks of occupancy data for the hotels.

Results.

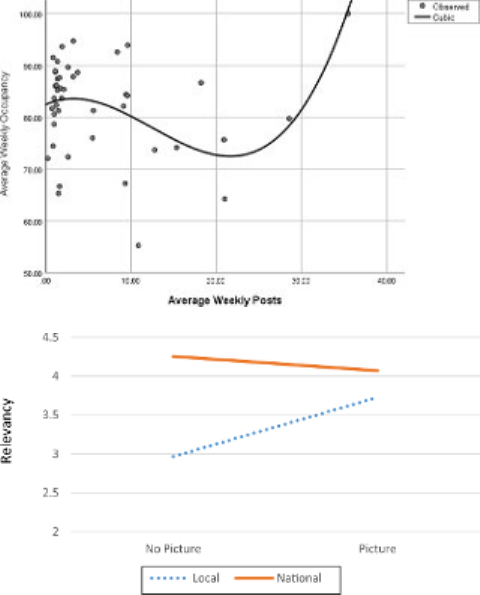

A sequential polynomial regression analysis was conducted on the average occupancy rate for average

social media posts. A linear model was first examined, which resulted in an insignificant regression,

followed by additional steps involving the next higher power of social media posts. As shown in Table

2, the quadratic component addition to the model produced a significant increase in fit, as did the

cubic addition. The cubic model added 7% r

2

to the 13% reflected in the quadratic model,

supporting H1, and the cubic model was adopted, F(3,40) = 3.336, p < 0.05, r

2

= 0.20; Y′ = 82.42 + 0.75X

− 0.13X

2

+ 0.004X

3

(Figure 2). The critical points for the cubic regression are at the local maxima of 3.43

posts at an occupancy rate of 83.62 and local minima of 18.24 posts, lowering the occupancy rate to

77.12, or 6.5 fewer rooms filled on average per night. Once hotels posted over three messages to social

media, occupancy rates tended to decline until they posted more than 18 messages [1], at which point

occupancy rates increased again.

Discussion

The results suggest that the relationship between social media posts and hotel occupancy rates is non-

linear, providing support for H1. Hotels should stay at or below two social media posts per week or

increase to above 20. Examining the nature of the data shows that those hotels posting greater

amounts to social media did so across multiple platforms (i.e. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook). Similarly,

those hotels posting once or twice a week were typically doing so from one platform. Those posting

between 2 and 20 posts per week across multiple platforms (most typically two) saw a negative effect

on occupancy rates. Next, the content of social media posts was analyzed to determine what kind of

social media posts are best for acquiring hotel customers.

Study 1B: content of posts analysis on occupancy

Procedure

Study 1B builds upon Study 1 A by examining the content of social media posts. A total of 332 social

media posts from the hotels in Study 1 A were examined over a five-week period prior to the average

occupancy rates across Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. The captured text and images of each social

media post were then moved into a file for coding on several variables: original content or shared from

another platform, image presence, mentioning of an event, how many replies, whether it contained

the hotel responses to a reply, generic (e.g. Happy Easter) or personalized (e.g. the hotel bistro’s menu)

content, the number of words and how many times the post was shared.

Coding instructions were created and given to a coder not associated with the research project. All

variables with no/yes responses, as well as the generic/personalized variable, were coded as 0/1. All

other responses were considered summation variables with the total number entered as the value (i.e.

number of replies on a post). After initial coding, the researchers reviewed the coding for accuracy and

agreement. Given that almost every variable was either no/yes or a summation (i.e. counting), there

was almost perfect agreement. Any discrepancies were discussed until an IRR of 100% was reached for

each variable.

Results

First, an ANOVA was conducted to assess the impact of a post’s originality (vs shared from another

source) on occupancy rates. The results show that a hotel has a higher average weekly occupancy

when it does not share posts from another source (i.e. the post is native to that platform and not

shared from another) (F(1,330) = 11.96, p < 0.001; M

original

= 82.06, M

shared

= 77.94). Additionally, posts

with an image were related to significantly higher occupancy rates than posts without an image

(F(1,330) = 9.71, p < 0.01; M

photo

= 81.70, M

none

= 75.85). There was also a significant interaction

between originality and photo presence (F(3,328) = 16.78, p < 0.001). When a post was not shared, the

main effect of having an image included in the post was not significant (F(1,271) = 0.004, p = 0.95;

M

photo

= 82.07, M

nophoto

= 81.92). However, when the post was shared to other platforms (F(1,57) =

25.03, p < 0.001), a significantly higher occupancy rate was evident when a photo was included (M =

79.86) than when no picture was included (M = 63.71). These results suggest that hotels should include

an image when sharing content across multiple platforms, lending support to H4.

Next, the mention of an event was examined and found to be negatively related to occupancy rates

(F(1,330) = 4.12, p < 0.05) M

noevent

= 82.51, M

event

= 80.59). To further examine this variable, events

were broken down to see whether the type of event mattered. There were nine categories of events:

no event, food/drink, hotel sponsored event, national sports team event, concert/festival, city-related

(e.g. a parade), major university-related (e.g. sporting events), holiday, and small local events (e.g. job

fair, fundraiser). The ANOVA for the type of event was also significant (F(8,323) = 4.92, p < 0.001),

where the type of event mentioned had an impact on occupancy rates. The highest occupancy rate was

related to the mention of a concert or festival (M = 84.41), which resulted in higher occupancy

compared to a food/drink post (M = 74.56, p < 0.001), national sports game (M = 70.52, p < 0.001) or

city-related event (M = 78.89, p < 0.05). The second-highest occupancy was related to holiday postings

(M = 83.53), which were also higher than food/drink (p < 0.001), national sports game (p < 0.001) and

city-related event (p < 0.05). The lowest occupancy was for posts related to a national sports game,

which was lower than all other posts except food/drink. Posting about no event (M = 81.67) had higher

occupancy than food/drink (p < 0.001) or national sports game (p < 0.001). Ultimately, if a hotel posts

about an event, it should post about a concert/festival or a holiday and should stay clear of posting

about a national sports game.

Several other analyses garnered insignificant results. Specifically, the relationship between responding

to a reply and occupancy rates was not significant (F(1,330) = 0.86, p = 0.35). Neither was a

personalized versus generic post (F(1,330) = 1.13, p = 0.29). Regressions were conducted for the total

number of words (F(1,330) = 0.08, β = −0.01, t = −0.29, p = 0.78), how many replies a post received

(F(1,330) = 0.03, β = −0.07, t = −0.18, p = 0.86), and how many times a post was shared (F(1,330) =

0.86, β = −0.14, t = −0.93, p = 0.35).

Discussion.

The results indicate posts should be original content not been previously shared on another platform

unless a photo is included. Additionally, posts should include an image about either non-events (e.g.

happy summer), a holiday or concerts and festivals. Hotels should avoid posting about food and drink

specials or events around the city (e.g. restaurant week), national sporting events or city events like

parades. The following two experimental studies explore the content of social media posts in more

detail.

Study 2: the mediating effect of relevancy

To further examine social media content and hotel stays, an experiment was conducted in Study 2 to

increase the level of control and understand how social media can impact occupancy through an

explanatory variable of relevancy (H2-H3).

Procedure 2

A total of 160 participants (56.3% female; 60% between 21 and 40 years old) completed the main

survey on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (set to US only, HIT approval of 95% or greater, and number of

HITs approved greater than 1,000) for payment. Each participant was told they would be shown a

social media page and to answer the questions that followed about that page. Participants were

randomly shown a social media page for a fictional hotel (The Cozy Inn) that either had a post related

to a national event (“Happy National Independence Day!”) or a local event (“Happy City Founder’s

Day!”). Neither post included an image. Participants were not told what city the hotel was in but were

told it was a city they did not live in but needed to stay in.

Participants were then asked survey questions regarding the relevancy of the post (α =

0.96; Miyazaki et al., 2005) (all constructs, items and reliabilities available in Table 3; descriptive

statistics and correlations available in Appendix 1) and their intent to stay at that hotel (α = 0.95;

adapted from Oliver and Swan, 1989).

Discriminant validity was assessed among the constructs using Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criterion

and was not problematic (see Appendix 1 for correlations between constructs and AVEs). Two

manipulation check questions (“The post was very specific to that city” and “This post seemed to be

only for people who live in the local area”) were asked on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly

disagree, 7 = strongly agree) and combined (r = 0.59, p < 0.01) to create a composite score. Participants

who saw the local post (M = 4.84) found it to be much more local in nature than those who saw the

national post (M = 3.14, F(1, 158) = 46.32, p < 0.001). Lastly, a question asked how realistic participants

found the social media page (1–7 on a Likert-type scale) and showed that participants found the

manipulations to be mostly realistic (M = 5.02) without differences between the two scenarios

(F(1,159) = 0.003, p = 0.96).

Results.

H2 predicts that a social media post about a national topic (compared to a local topic) will have a

positive relationship with relevancy. A significant ANOVA (F(1,158) = 90.93, power > 0.96, p < 0.001)

lends support to this hypothesis. Viewers found the post about a national event to be significantly

more relevant (M = 5.18) than a local event (M = 2.79). H3 was supported as more relevant posts led to

a greater likelihood to stay at that hotel (B = 0.20, t = 0.31, power > 0.82, p < 0.001). PROCESS (Hayes,

2018) model 4 was run for mediation analysis. The indirect effect (ab = 0.73, 95% CI: [0.44, 1.07]) was

significant, showing that a national social media post can lead to an increase in intentions to stay at a

hotel as explained through the relevancy of the post.

Another possible explanation, however, could be that a local post makes viewers feel either like they

are intruding or that they do not belong. An alternative model was tested with intrusiveness (α =

0.97; Li et al., 2002) and sense of belonging (α = 0.87; Pechmann et al., 2003) as explanatory

mechanisms. The relationship between post type and intrusiveness was not significant (F(1,158) =

3.14, p = 0.08); neither was the relationship between intrusiveness and stay intentions (B = 0.09, t =

1.41, p = 0.16). The post type did not have a significant relationship with sense of belonging (F(1,158) =

2.92, p = 0.09), but a sense of belonging did have a positive and significant relationship with stay

intentions (B = 0.69, t = 9.69, p < 0.001). However, as the relationship between post type and belonging

was not significant, the mediation analysis was also not significant (ab = 0.21, 95% CI: [−0.04, 0.46]).

Therefore, relevancy is the best-suited mediator to explain how the content of a post can impact stay

intentions.

Discussion.

As hypothesized, a more inclusive, national post was perceived as more relevant than a post about a

local event, and relevancy led to greater stay intentions. Additionally, relevancy acted as a mediator

between post type and stay intentions. The post type did not have a significant impact on either

intrusiveness or sense of belonging. However, belonging did have a positive relationship with stay

intentions, suggesting a possible avenue for future research on social media post content. The results

suggest that relevancy is the best mediator variable when trying to predict hotel stays from social

media posts, supporting H2 and H3.

Study 3: the moderating effect of visual inclusion

Study 3 was conducted to test the generalizability of Study 2 by examining relevancy of posts in a

different context and confirming support for H2-3. Additionally, Study 3 was designed to

assess H4 directly by investigating the moderating impact of including an image within a post.

Procedure [3

A total of 253 participants (55.7% female; 55.7 between 21 and 40 years old) completed the survey,

with a similar setup to Study 2. Each participant was told they would be shown a social media page and

to answer the questions that followed about the page. They were then randomly shown a social media

page for a fictional hotel (The Modern Hotel) that either had a post related to a national or local

football game. The post was either accompanied by an image (a close up of a football and white

helmet on a non-identifiable field) or not. Participants were not told what city the hotel was in, only

that it was a city they did not live in but needed to stay in.

Participants were then asked survey questions regarding the relevancy of the post (α = 0.97) (all

constructs, items and reliabilities available in Table 3) and their intent to stay at that hotel (α = 0.96).

Discriminant validity was assessed as in Study 2 and was not problematic (see Appendix 1 for the

correlations between constructs and AVEs). Two manipulation check questions were asked as outlined

in Study 2 and combined (r = 0.68, p < 0.01) to create a composite score. Participants who saw the local

football post (M = 5.21) found it to be much more local in nature than those who saw the national post

(M = 3.47, F(1,251) = 77.54, p < 0.001). Participants also answered a realism question (1–7 on a Likert-

type scale) and found the scenarios to be realistic overall (M = 4.94). No differences were found to

exist between groups (F(3, 249) = 0.50, p = 0.68).

Results

H2 predicts that a social media post about a local event will have lower relevancy than a post about a

national event. A significant main effect (F(1, 249) = 12.01, power > 0.99, p < 0.001) supports this as

people who saw the national football post (M = 4.16) felt it was more relevant than those who saw the

local football post (M = 3.35). H3 predicts that relevancy has a positive relationship with intentions to

stay at the hotel (B = 0.31, t = 8.50, power > 0.99, p < 0.001) and is also supported by a significant and

positive effect. These results support H2 and H3 and replicate findings from Study 2.

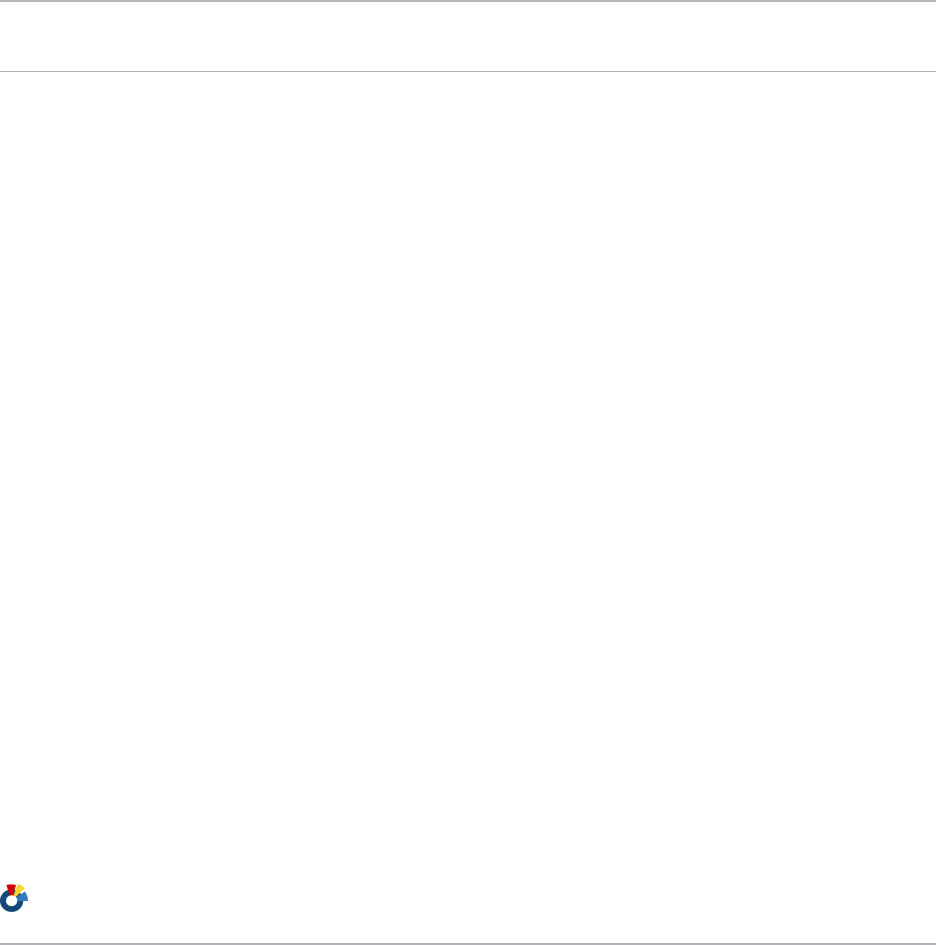

H4 examines the interaction between post type, the presence of an image and relevancy. The presence

of an image did not have a significant main effect (F(1, 249) = 1.49, p = 0.22) on relevancy, but the

interaction of post type and image was significant (F(1, 249) = 4.03, power > 0.95, p < 0.05; see Figure

3). When there is no picture alongside the text in the post, there is a significant effect of national

versus local content (F(1, 123) = 15.23, power > 0.99, p < 0.001). When a picture was absent, the post

about a local event (M = 2.97) was found to be significantly less relevant than a post about a national

event (M = 4.26). However, this effect was not evident when a picture was present (F(1, 126) =

1.06, p = 0.31; M

national

=4.07, M

local

= 3.73).

PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) model 7 tested the moderated mediation of relevancy. The index of moderated

mediation was significant (0.31, 95% CI: [−0.63, −0.01]), indicating differences between the indirect

effects at the moderator level. When a picture was absent, a national post led to greater stay

intentions as explained through relevancy (ab = 0.42, 95% CI: [0.20, 0.67]) but not when a picture was

present (ab = 0.11, 95% Ci: [−0.10, 0.36]).

Discussion

Study 3 replicates our findings from Study 2 and supports H4 by examining a moderator of image

presence. The impact of a local or national event on relevancy can be negated when the post is

accompanied by an image. Including an image with a post about a local event can help the post seem

more relevant, increasing the likelihood of staying at the hotel.

General discussion

Consumers are increasingly using traditional social media platforms to research services in their

decision-making process (Beer, 2018) and stay informed. For example, 90% of social media users follow

a brand on Instagram to stay up to date with the company (Zote, 2020). Despite the importance of

social media, the majority of companies are unsure whether they have implemented successful social

media strategies (Guttmann, 2019). Our findings indicate that a purposeful social media strategy

influences intentions to stay at the focal hotel, highlighting the role of the quantity and content of

social media posts.

The results contribute to social impact theory by illustrating that a company’s social media posts can

generate social influence on an individual’s consumption behavior. First, the relationship between the

number of posts and occupancy is non-linear. Specifically, the number of posts has a positive

relationship with occupancy until 3.43 posts per week, at which point the relationship turns negative.

This is in line with social impact theory’s premise that the number of influencers becomes less

impactful as frequency increases (Latané, 1981) and with research suggesting that social influences do

not have to be linear (Stacy et al., 1992). An overabundance of posts spreads influence too thin for any

one post, leading to a drop in performance as indicated by fewer hotel stays. Yet, as the number of

posts exceeded 18.24 per week, posts started to positively influence hotel occupancy again. Consistent

with social impact theory, there should be a re-strengthening of influence as the number of sources

starts to increase and the immediacy of the effect starts to become more frequent (Latané,

1981). Additionally, the content of posts was examined, indicating that original posts about a concert,

festival, holiday or non-event that include an image are the most beneficial to occupancy. Posts that

are about food/drink specials, national sports games or local events resulted in the lowest occupancy

rates.

Previous research has shown that information relevancy can impact perceptions of quality (Carlson et

al., 2018) and increase engagement (Lee et al., 2020). The findings presented here add to relevancy

literature and social impact theory (Latané, 1981) by showing that social impact theory can be used in

social media contexts to explain how relevancy increases the strength of influence. Social influence is

most impactful when it is relevant to the influenced party, which can be accomplished by posting

about a broader geographical topic rather than specific locations. Posting locally themed content

places the viewer into an out-group (Tajfel, 1979), which lessens their identification with the hotel.

Posting about a local matter caused the viewer to feel the post was less relevant, thus reducing the

likelihood to stay. Social impact theory (Latané, 1981) posits that influence is determined by strength,

immediacy and number of sources. Combined with elements of social identity theory, the results show

that relevancy of information from a source can significantly impact influence, adding to the tenets of

social impact theory.

Lastly, we contribute to social impact theory by showing that influence can be altered by the inclusion

of a picture. Previous research has shown that text with an image is more influential than text alone

(Yoon, 2018). The findings here indicate that when an image is included with a text post, relevancy was

increased for a local post and the relationship between local/national post and relevancy was no

longer significant. This is likely due to the image helping the viewer create an identity (Lindahl and

Öhlund, 2013) that is more in line with the identity of the poster (Pittman and Reich, 2016). With 90%

of US companies being involved with social media as a marketing tool (Guttmann, 2019), it is important

to know the best means to influence social targets.

Managerial implications

These findings also have important practical implications for social media marketers. Prior research has

produced conflicting findings when recommending how often a brand should be posting (Mariani et

al., 2016; Mariani et al., 2018). Social media managers should ensure their accounts post between 1

and 3 times per week (either three times on one platform or one time on three platforms) or more

than 19 times per week across multiple platforms. These posts should be original (i.e. not shared from

another platform) about a concert, festival, holiday or national event and include a picture.

Furthermore, posts should not be about food/drink specials or local stories. As with other advertising

messages, communications seen via social media should be relevant to the brand (Alalwan,

2018), website and task (Resnick and Albert, 2016).

The findings show that the communications should also be relevant to the social media viewers.

Increasing relevancy can increase product/service usage intent. Social media managers should be

careful not to exclude viewers by making posts too specific and exclusive. Users tested here felt that

national geographical content was more relevant than location-specific posts. Including a picture with

a post can help a viewer find more relevancy in the post, even if the post’s text alone would be seen as

exclusionary.

Limitations and future research

The current research has its limitations and presents viable opportunities for future research. The data

were limited by the hotels in the dataset collected. Future research could look at whether the guests

who stayed at the hotels used social media in making their decision. Since the data were collected in

the spring, future research could examine the possibility of a time-of-year effect. Additionally, because

this research only examines the hotel industry, future research could expand to other service industries

to see whether the results hold.

There are also many other variables of interest, such as sound or animation, that could be used in

isolation or in combination with the variables examined here to determine their effectiveness and

impact on relevancy and stay intentions. The images used in Study 3 did not include people, which

could impact in-group feelings (Brown et al., 2006).

For most companies with a social media presence, it is important to determine best practices of

communication with consumers. More than two-thirds of companies, however, are concerned about

their ability to assess the effectiveness of their social media efforts (Guttmann, 2019). The research

presented here shows the direct effects of social media posts on hotel occupancy rates while outlining

several practical ways to increase the relevancy of such posts.

Figures

Figure 1 Conceptual model

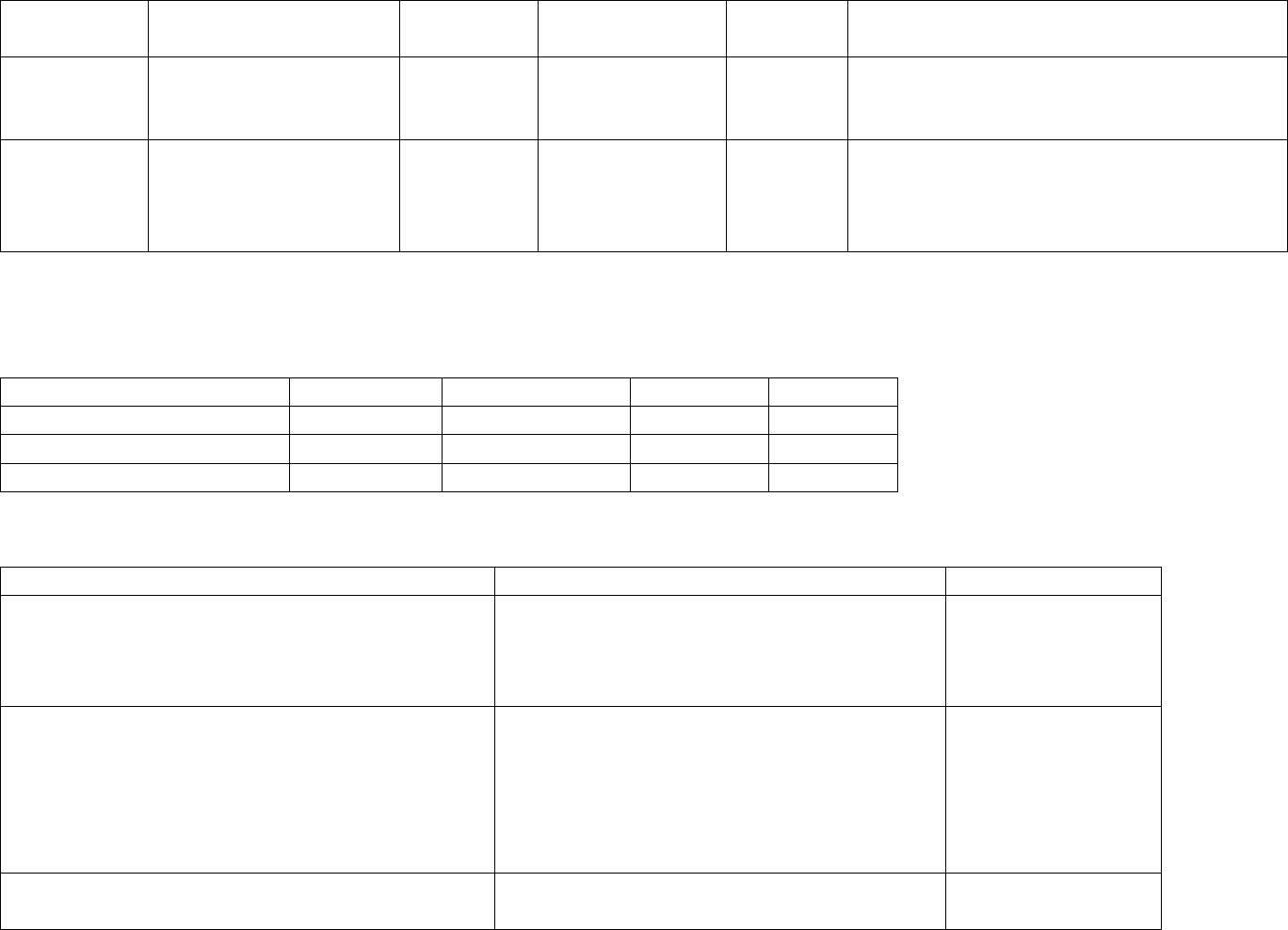

Table 1 Review of relevant literature – services and social media

Authors

Theoretical foundations

Focus

Medium

Industry

Findings

Paulin et

al. (2014)

Self-determination

theory

Traditional

SN

Facebook

Nonprofit

There is a positive association between

support for social causes and efficient social

media use. It is better to appeal to the

benefits to others than benefits to the self

when gaining support for social causes

through social media

Kim et

al. (2015)

Online

Reviews

TripAdvisor,

Priceline,

Hotels.com,

Expedia, & Yelp

Hotel

Overall ratings are the most salient predictor

of hotel performance, followed by response

to negative comments

Leung et

al. (2015)

Attitude-Toward-the-Ad

Model; Attitude-Toward-

the-Website/Social-

Media-Page Model

Traditional

SN

Facebook &

Twitter

Hotel

Hotel customers’ social media experiences

influence their attitudes-toward-social-

media-site, which in turn influences their

attitudes-toward-hotel-brand, affecting

booking intentions and intentions to spread

eWOM

Choi et

al. (2016)

Uses and Gratification

Theory

Traditional

SN

Facebook

Hotel

Information, convenience, and self-

expression are antecedents for user

satisfaction with the hotel’s Facebook page,

where satisfaction positively influences

intentions to stay at the hotel in the future

Leung and

Tanford

(2016)

Social Identity Theory;

Social Influence Model;

Uses and Gratification

Model

Traditional

SN

Facebook

Hotel

Social influence factors (i.e., compliance,

internalization, and identification) had

different effects on attitudes toward and

behavioral intentions to like hotel Facebook

pages

Viglia et

al. (2016)

Dual Process Theory

Travel SN/

Online

Reviews

Booking.com,

TripAdvisor, &

Venere.com

Hotel

Review score and number of reviews has a

positive impact on hotel occupancy rates.

The number of reviews has decreasing

returns, where the higher the number of

reviews, the lower the beneficial effect on

occupancy rate

Xie et

al. (2016)

Managerial response

Travel SN

TripAdvisor

Hotel

Managerial response increases stars in

Tripadvisor ratings for sampled hotels and

increases the volume of subsequent

consumer eWOM. Managerial response

moderates the influence of ratings and

volume of consumer eWOM on hotel

performance

Garrigos-

Simon et

al. (2017)

Crowdsourcing

Travel SN

Booking.com

Hotel

Direct and positive opinions of the crowd on

the amount of hotel sales do not depend on

physical intermediaries, nor on the impact

that this has on the performance dimensions

of hotels

Kim and Park

(2017)

Regulatory Focus Theory

Travel SN/

Online

Reviews

TripAdvisor

Hotel

Social media review ratings are more

significant predictors than traditional

customer satisfaction for explaining hotel

performance metrics

Abney et

al. (2017)

Justice Theory

Traditional

SN

Twitter

Restaurant

Customized social media recovery responses

positively impact consumers’ evaluations of

service recovery satisfaction, leading to

greater consumer behavioral intentions

Sorensen et

al. (2017)

Customer Engagement

Theory

Traditional

SN

Facebook;

Twitter; YouTube

Nonprofit

Characteristics of social media posts need to

be member-centric. The tone and language

of posts can be leveraged to engage

members effectively

Huang et

al. (2018)

Narrative Transportation

Theory; Transportation-

Imagery Model

Traditional

SN

Instagram

Hotel

Within the luxury hotel industry,

comprehension fluency, imagery fluency, and

transportability positively affect narrative

transportation. Narrative transportation

leads to positive affect, brand social network

attitudes, and visit intentions

Kim and Chae

(2018)

Resource and

Capabilities-Based

Perspective

Traditional

SN

Twitter

Hotel

There is a positive association between a

hotel’s resources and Twitter use, and a

positive association between Twitter use by

hotels and their RevPAR

Torres et

al. (2018)

Social Identity Theory;

Complexity Theory

Traditional

SN

Facebook

Banking

Social media activities increase consumers’

willingness to pay a premium price in the

banking industry. This effect is fully mediated

by the role of consumer-brand identification

Carlson et

al. (2018)

Consumption Values

Theory

Traditional

SN

Facebook

Misc.

Online service design characteristics in social

media posts encourage an identified set of

customer value perceptions that influence

customer feedback and collaboration

intentions

Bigné et

al. (2019)

Information Processing

Approach; Consumer

Socialization Theory

Traditional

SN

Twitter

Hotel

The number of retweets and replies by users

and the number of event tweets, tourist

attraction tweets, and retweets by direct

marketing organizations can predict the hotel

occupancy rate for a given destination

Diffley and

McCole

(2019)

Service-Dominant Logic

Traditional

SN; Travel

SN

Hotel

Networked interactions facilitated by social

networks influence the marketing activities

of hotels (i.e., deeper connections and co-

creating value with customers to enhance

the market offerings and promotional

activities of the firm)

Moon et

al. (2019)

False Information Bias

Travel SN/

Online

Reviews

TripAdvisor,

Priceline,

Hotels.com,

Expedia, & Yelp

Hotel

Open- versus closed-review posting policies

play different roles in creating social media

bias. Using the hotel industry, a trust

measure was found to serve as a correction

factor that reduces social media bias

Tsiotsou

(2019)

Hofstede’s Framework

Travel SN/

Online

Reviews

TripAdvisor

Hotel

Cultural differences in overall service

evaluations and attributes (value, location,

sleeping quality, rooms, cleanliness, and

service) were found among tourists from

various European regions

Moon et

al. (2020)

Reality Monitoring

Theory

Online

reviews

Hotel

Real-world hotel reviews were analyzed to

detect fake reviews and identify the hotel

and review characteristics influencing review

fakery (e.g. star rating, franchise hotel, hotel

size, room price, review timing, and review

rating)

Lee et

al. (2020)

Theory of Customer

Engagement

Traditional

SN

Facebook; Twitter

Hospital

There is a positive association between a

hospital’s social media engagement and

experiential quality

Bacile (2020)

Customer Compatibility

Management Theory

Traditional

SN

Facebook

Restaurant

Perceptions of a firm’s service climate are

negatively affected by online incivility but

only when incivility produces perceptions of

customer-to-customer injustice

Notes: SN = Social Network; Traditional SN = Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, or MySpace; Travel SN = Travel-related websites that allow for

users to post reviews and ratings

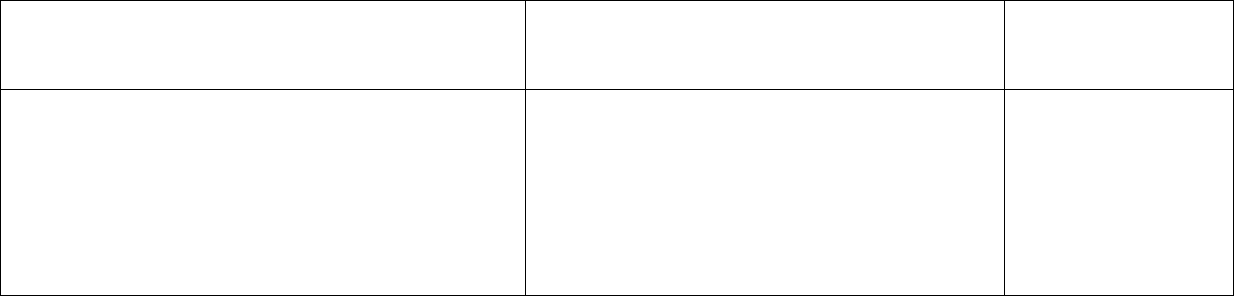

Table 2 Predicting occupancy from number of social media posts

Step

R

2

F for R

2

df

p

1: Linear

0.004

0.15

1, 42

0.70

2: Quadratic

0.13

2.99

2, 41

0.06

3: Cubic

0.20

3.36

3, 40

0.03

Table 3 Constructs, items and reliabilities

Construct and definition

Items

Reliability Study 2/ 3

Relevance

Miyazaki et al. (2005)

Very relevant

Very useful

Very important

0.96/ 0.97

Belonging

Pechmann et al. (2003)

I really fit in there

People would accept me there

What I offer is valued there

It made me feel like I have a place in this world

I would feel a part of mainstream society there

0.87/ na

Intrusiveness

Li et al. (2002)

I felt like I was interfering

0.97/ na

I felt like I was intruding

I felt like I was being invasive

I felt like I was being obtrusive

Stay Intentions

The likelihood of the customer staying at the hotel

Oliver and Swan (1989)

Not at all likely/very likely

Non-existent/existent

Improbable/probable

Impossible/possible

Uncertain/certain

Probably not/probably

0.95/ 0.96

Table A1. Study 2: Mediation

AVE

Correlations

Construct

M

SD

1

2

3

Relevance (1)

3.95

1.98

0.86

Belonging (2)

4.43

1.13

0.47

0.43

**

Intrusiveness (3)

2.38

1.63

0.82

0.29

**

0.30

**

Stay intentions (4)

4.94

1.27

0.65

0.31

**

0.61

**

0.11

Notes: AVE = average variance extracted

**p < 0.01

Table A2. Study 3: Local × Picture

AVE

Correlation

Construct

M

SD

1

Relevance (1)

3.77

1.92

0.81

Stay intentions (2)

5.28

1.25

0.64

0.47**

Note: AVE = average variance extracted

** p <0.01

Notes

1 Similar results were seen when analyzing the weeks individually or when stacking the data to have 88

hotel-to-occupancy dyads.

2 A pretest was conducted with similar results to the main study.

3 A pretest was conducted with similar results to the main study.

References

Abney, A.K., Pelletier, M.J., Ford, T.R.S. and Horky, A.B. (2017), “#IHateYourBrand: adaptive service

recovery strategies on Twitter”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 281-294.

Alalwan, A.A. (2018), “Investigating the impact of social media advertising features on customer

purchase intention”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 42, pp. 65-77.

Ashley, C. and Tuten, T. (2015), “Creative strategies in social media marketing: an exploratory study of

branded social content and consumer engagement”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 32 No. 1,

pp. 15-27.

Bacile, T.J. (2020), “Digital customer service and customer-to-customer interactions: investigating the

effect of online incivility on customer perceived service climate”, Journal of Service

Management, Vol. 31 No. 3, pp. 441-464.

Barnhart, B. (2020), “20 Social media ideas to keep your BRAND'S feed fresh”, available

at: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-ideas/

Beer, C. (2018), “Social browsers engage with brands”, available

at: https://blog.globalwebindex.com/chart-of-the-day/social-browsers-brand/

Berger, C.R. and Calabrese, R.J. (1975), “Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: toward a

developmental theory of interpersonal communication”, Human Communication Research,

Vol. 1 No. 2, pp. 99-112.

Better Business Bureau (2019), “How social media is influencing consumers to make

purchases”, available at: https://medium.com/@BBBNWP/how-social-media-is-influencing-

consumers-to-make-purchases-ad2d767eaf7a

Bigné, E., Oltra, E. and Andreu, L. (2019), “Harnessing stakeholder input on twitter: a case study of

short breaks in Spanish tourist cities”, Tourism Management, Vol. 71, pp. 490-503.

Broderick, A.J. (2007), “A cross-national study of the individual and national–cultural nomological

network of consumer involvement”, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 24 No. 4, pp. 343-374.

Brown, L.M., Bradley, M.M. and Lang, P.J. (2006), “Affective reactions to pictures of ingroup and

outgroup members”, Biological Psychology, Vol. 71 No. 3, pp. 303-311.

Campbell, D.E. and Wright, R.T. (2008), “Shut-up I don’t care: understanding the role of relevancy and

interactivity on customer attitudes toward repetitive online advertising”, Journal of Electronic

Commerce Research, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 62-76.

Carlson, J., Rahman, M., Rosenberger, I.I.I., P.J. and Holzmüller, H.H. (2016), “Understanding communal

and individual customer experiences in group-oriented event tourism: an activity theory

perspective”, Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 32 Nos 9/10, pp. 900-925.

Carlson, J., Rahman, M., Voola, R. and De Vries, N. (2018), “Customer engagement behaviours in social

media: capturing innovation opportunities”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 83-

94.

Chang, Y. (2018), “Perceived message consistency: explicating how brand messages being processed

across multiple online media”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 85, pp. 125-134.

Choi, E.K., Fowler, D., Goh, B. and Yuan, J. (2016), “Social media marketing: applying the uses and

gratifications theory in the hotel industry”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management,

Vol. 25 No. 7, pp. 771-796.

Cialdini, R.B. and Goldstein, N.J. (2004), “Social influence: compliance and conformity”, Annual Review

of Psychology, Vol. 55 No. 1, pp. 591-621.

Clement, J. (2020), “U.S. number of social media users 2023”, available

at: www.statista.com/statistics/278409/number-of-social-network-users-in-the-united-

states/ (accessed October 26, 2020).

De Keyzer, F., Dens, N. and De Pelsmacker, P. (2021), “How and when personalized advertising leads to

brand attitude, click, and WOM intention”, Journal of Advertising, pp. 1-18.

Diffley, S. and McCole, P. (2019), “The value of social networking sites in hotels”, Qualitative Market

Research: An International Journal, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 114-132.

Ellis-Chadwick, F. and Doherty, N.F. (2012), “Web advertising: the role of e-mail marketing”, Journal of

Business Research, Vol. 65 No. 6, pp. 843-848.

Esmark Jones, C.L., Barney, C. and Farmer, A. (2018), “Appreciating anonymity: an exploration of

embarrassing products and the power of blending in”, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 94 No. 2,

pp. 186-202.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables

and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50.

Garrigos-Simon, F.J., Galdon, J.L. and Sanz-Blas, S. (2017), “Effects of crowdvoting on hotels: the

booking.com case”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management,

Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 419-437.

Gurrieri, L. and Drenten, J. (2019), “Visual storytelling and vulnerable health care consumers:

normalising practices and social support through Instagram”, Journal of Services Marketing,

Vol. 33 No. 6, pp. 702-720.

Guttmann, A. (2019), “U.S. social media marketing reach 2019”, available

at: www.statista.com/statistics/203513/usage-trands-of-social-media-platforms-in-marketing/

Hayes, A. (2018), Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A

Regression-Based Approach, The Guilford Press, New York, NY.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Wiertz, C. and Feldhaus, F. (2015), “Does Twitter matter? the impact of

microblogging word of mouth on consumers’ adoption of new movies”, Journal of the Academy

of Marketing Science, Vol. 43 No. 3, pp. 375-394.

Henninger, C.E., Alevizou, P.J. and Oates, C.J. (2017), “IMC, social media, and UK fashion micro-

organisations”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 668-691.

Howard, D.J. and Kerin, R.A. (2004), “The effects of personalized product recommendations on

advertisement response rates: the ‘try this. It works!’ technique”, Journal of Consumer

Psychology, Vol. 14 No. 3, pp. 271-279.

Huang, M.H. (2006), “Flow, enduring, and situational involvement in the web environment: a tripartite

second-order examination”, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 383-411.

Huang, R., Ha, S. and Kim, S.H. (2018), “Narrative persuasion in social media: an empirical study of

luxury brand advertising”, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 274-

292.

Hutter, K., Hautz, J., Dennhardt, S. and Füller, J. (2013), “The impact of user interactions in social media

on brand awareness and purchase intention: the case of MINI on Facebook”, Journal of Product

& Brand Management, Vol. 22 Nos 5/6, pp. 342-351.

Jung, A.R. (2017), “The influence of perceived ad relevance on social media advertising: an empirical

examination of a mediating role of privacy concern”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 70,

pp. 303-309.

Kim, W. and Chae, B. (2018), “Understanding the relationship among resources, social media use and

hotel performance: the case of Twitter use by hotels”, International Journal of Contemporary

Hospitality Management, Vol. 30 No. 9, pp. 2888-2907.

Kim, W.G., Lim, H. and Brymer, R.A. (2015), “The effectiveness of managing social media on hotel

performance”, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Vol. 44, pp. 165-171.

Kim, W. and Park, S. (2017), “Social media review rating versus traditional customer

satisfaction”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 29 No. 2,

pp. 784-802.

Kumar, A., Bezawada, R., Rishika, R., Janakiraman, R. and Kannan, P.K. (2016), “From social to sale: the

effects of firm-generated content in social media on customer behavior”, Journal of Marketing,

Vol. 80 No. 1, pp. 7-25.

Latané, B. (1981), “The psychology of social impact”, American Psychologist, Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 343-356.

Leach, M.P. and Liu, A.H. (1998), “The use of culturally relevant stimuli in international

advertising”, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 15 No. 6, pp. 523-546.

Ledbetter, A.M. and Redd, S.M. (2016), “Celebrity credibility on social media: a conditional process

analysis of online self-disclosure attitude as a moderator of posting frequency and parasocial

interaction”, Western Journal of Communication, Vol. 80 No. 5, pp. 601-618.

Lee, Y., In, J. and Lee, S.J. (2020), “Social media engagement, service complexity, and experiential

quality in US hospitals”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 34 No. 6, pp. 833-845.

Leung, X.Y. and Bai, B. (2013), “How motivation, opportunity, and ability impact travelers’ social media

involvement and revisit intention”, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, Vol. 30 Nos 1/2,

pp. 58-77.

Leung, X.Y., Bai, B. and Stahura, K.A. (2015), “The marketing effectiveness of social media in the hotel

industry: a comparison of Facebook and Twitter”, Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research,

Vol. 39 No. 2, pp. 147-169.

Leung, X.Y. and Tanford, S. (2016), “What drives Facebook fans to ‘like’ hotel pages: a comparison of

three competing models”, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, Vol. 25 No. 3,

pp. 314-345.

Li, H., Edwards, S.M. and Lee, J.H. (2002), “Measuring the intrusiveness of advertisements: scale

development and validation”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 37-47.

Lindahl, G. and Öhlund, M. (2013), “Personal branding through imagification in social media identity

creation and alteration through images”, unpublished master’s thesis, Stockholm

University, Sweden.

Lock, S. (2020), “Hotel industry: revPAR by region 2019”, available

at: www.statista.com/statistics/245763/revenue-per-available-room-of-hotels-worldwide-by-

region/ (accessed October 26, 2020).

Mariani, M.M., Di Felice, M. and Mura, M. (2016), “Facebook as a destination marketing tool: evidence

from Italian regional destination management organizations”, Tourism Management, Vol. 54,

pp. 321-343.

Mariani, M.M., Mura, M. and Di Felice, M. (2018), “The determinants of Facebook social engagement

for national tourism organizations’ Facebook pages: a quantitative approach”, Journal of

Destination Marketing & Management, Vol. 8, pp. 312-325.

Miyazaki, A.D., Grewal, D. and Goodstein, R.C. (2005), “The effect of multiple extrinsic cues on quality

perceptions: a matter of consistency”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 32 No. 1, pp. 146-

153.

Moon, S., Kim, M.Y. and Bergey, P.K. (2019), “Estimating deception in consumer reviews based on

extreme terms: comparison analysis of open vs. closed hotel reservation platforms”, Journal of

Business Research, Vol. 102, pp. 83-96.

Moon, S., Kim, M.Y. and Iacobucci, D. (2020), “Content analysis of fake consumer reviews by survey-

based text categorization”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 38 No. 2.

Oliver, R.L. and Swan, J.E. (1989), “Consumer perceptions of interpersonal equity and satisfaction in

transactions: a field survey approach”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 53 No. 2, pp. 21-35.

Pan, Z., Lu, Y., Wang, B. and Chau, P.Y. (2017), “Who do you think you are? Common and differential

effects of social self-identity on social media usage”, Journal of Management Information

Systems, Vol. 34 No. 1, pp. 71-101.

Paulin, M., Ferguson, R.J., Jost, N. and Fallu, J.M. (2014), “Motivating millennials to engage in

charitable causes through social media”, Journal of Service Management, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 334-

348.

Pechmann, C., Zhao, G., Goldberg, M.E. and Reibling, E.T. (2003), “What to convey in antismoking

advertisements for adolescents: the use of protection motivation theory to identify effective

message themes”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 67 No. 2, pp. 1-18.

Perez-Vega, R., Waite, K. and O'Gorman, K. (2016), “Social impact theory: an examination of how

immediacy operates as an influence upon social media interaction in Facebook fan pages”, The

Marketing Review, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 299-321.

Perrin, A. (2020), “Social media usage: 2005-2015”, available

at: www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/10/08/social-networking-usage-2005-2015/ (accessed

October 26, 2020).

Peruta, A. and Shields, A.B. (2017), “Social media in higher education: understanding how colleges and

universities use Facebook”, Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 131-

143.

Petty, R.E. and Cacioppo, J.T. (1986), “The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion”, Communication

and Persuasion, Springer, New York, NY, pp. 1-24.

Pittman, M. and Reich, B. (2016), “Social media and loneliness: why an Instagram picture may be worth

more than a thousand Twitter words”, Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 62, pp. 155-167.

Quesenberry, K.A. (2018), “The basic social MEDIA mistakes companies still make”, available

at: https://hbr.org/2018/01/the-basic-social-media-mistakes-companies-still-make (accessed

February 21, 2021).

Rehman, Z.U., Baharun, R. and Salleh, N.Z.M. (2020), “Antecedents, consequences, and reducers of

perceived risk in social media: a systematic literature review and directions for further

research”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 74-86.

Resnick, M.L. and Albert, W. (2016), “The influences of design esthetic, site relevancy and task

relevancy on attention to banner advertising”, Interacting with Computers, Vol. 28 No. 5,

pp. 680-694.

Sorensen, A., Andrews, L. and Drennan, J. (2017), “Using social media posts as resources for engaging

in value co-creation: the case for social media-based cause brand communities”, Journal of

Service Theory and Practice, Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 898-922.

Stacy, A.W., Newcomb, M.D. and Bentler, P.M. (1992), “Interactive and higher-order effects of social

influences on drug use”, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 33 No. 3, pp. 226-241.

Tajfel, H. (1979), “Individuals and groups in social psychology”, British Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 183-190.

Torres, P., Augusto, M. and Wallace, E. (2018), “Improving consumers’ willingness to pay using social

media activities”, Journal of Services Marketing, Vol. 32 No. 7, pp. 880-896.

Trampe, D., Stapel, D.A., Siero, F.W. and Mulder, H. (2010), “Beauty as a tool: the effect of model

attractiveness, product relevance, and elaboration likelihood on advertising

effectiveness”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 27 No. 12, pp. 1101-1121.

Tsiotsou, R.H. (2019), “Rate my firm: cultural differences in service evaluations”, Journal of Services

Marketing, Vol. 33 No. 7, pp. 815-836.

Turner, J.C. (1991), Social Influence, Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co, Pacific Grove, Ca.

Viglia, G., Minazzi, R. and Buhalis, D. (2016), “The influence of e-word-of-mouth on hotel occupancy

rate”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 28 No. 9, pp. 2035-

2051.

Xia, L. and Bechwati, N.N. (2008), “Word of mouse: the role of cognitive personalization in online

consumer reviews”, Journal of Interactive Advertising, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 3-13.

Xie, K.L., Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Amrik, S. and Lee, S. (2016), “Effects of managerial response on consumer

eWOM and hotel performance: evidence from TripAdvisor”, International Journal of

Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 28 No. 9, pp. 2013-2034.

Yoon, S. (2018), “A sociocultural approach to Korea wave marketing performance: cross-national

adoption of arguments on foreign cultural products in a social media context”, Journal of

Marketing Theory and Practice, Vol. 26 Nos 1/2, pp. 196-209.

Zeng, F., Huang, L. and Dou, W. (2009), “Social factors in user perceptions and responses to advertising

in online social networking communities”, Journal of Interactive Advertising, Vol. 10 No. 1,

pp. 1-13.

Zhang, X., Li, S., Burke, R.R. and Leykin, A. (2014), “An examination of social influence on shopper

behavior using video tracking data”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 78 No. 5, pp. 24-41.

Zote, J. (2020), “55 Critical social media statistics to fuel your 2020 strategy”, available

at: https://sproutsocial.com/insights/social-media-statistics/.

Further reading

Li, H. and Bukovac, J.L. (1999), “Cognitive impact of banner ad characteristics: an experimental

study”, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Vol. 76 No. 2, pp. 341-353.