2023-2028 Texas State

Health Plan

As Required by

Texas Health and Safety Code

Section 104.021-104.026

Statewide Health Coordinating

Council

November 2022

This report was prepared at the direction of the Statewide Health

Coordinating Council. The opinions and recommendations

expressed in this report are that of the Council and do not reflect

the views of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission,

Department of State Health Services, or Texas Health and Human

Services System

2

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ................................................................................... 2

1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 4

2. Background ....................................................................................... 6

3. Access to Care ................................................................................... 7

Defining Access to Care ....................................................................... 7

Populations with Poor Access ................................................................ 9

Texas Populations with Poor Access ................................................. 10

COVID-19 and Access ........................................................................ 13

Nationwide Access ........................................................................ 13

Access in Texas ............................................................................ 14

Race & Ethnicity ........................................................................... 14

Strategies for Improving Access .......................................................... 14

Covering More Texans ................................................................... 15

Provider Participation in Medicaid .................................................... 16

Other Policy Considerations ............................................................ 17

Policy Developments ..................................................................... 17

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature, the Governor, and Executive

Branch Agencies ........................................................................... 18

4. Rural Health .................................................................................... 23

Health Outcomes in Rural Areas .......................................................... 23

COVID-19 ................................................................................... 23

Emergency Medical Services ........................................................... 24

Teleservices................................................................................. 24

Older Adults in Rural Areas ............................................................ 24

Challenges for Low-Income and Uninsured Populations in Rural Areas ... 25

Hospital and Nursing Facility Closures .................................................. 25

Providers ......................................................................................... 26

Older Providers ............................................................................ 27

Obstetric Services......................................................................... 27

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature, the Governor, and Executive

Branch Agencies ........................................................................... 27

5. Mental Health and Behavioral Health Workforce ............................. 31

Background ..................................................................................... 31

Texas’ Need for Mental Health Services ................................................ 34

Children ...................................................................................... 34

Adolescents ................................................................................. 34

Adults ......................................................................................... 35

Texas’ Mental Health Workforce .......................................................... 36

3

Mental Health Workforce by Profession Among Racial/Ethnic Categories,

Texas, 2019 ............................................................................ 36

Overview of Mental Health Workforce by Profession ........................... 37

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature, the Governor, and Executive

Branch Agencies ........................................................................... 45

6. Teleservices and Technology ........................................................... 53

Defining Teleservices ......................................................................... 53

Use of Teleservices in Texas ............................................................... 53

COVID-19 and the Expansion of Teleservices ......................................... 54

Benefits of Teleservices ...................................................................... 55

Access to Teleservices ....................................................................... 56

Access in Rural Counties ................................................................ 56

Providers’ Ability to Deliver Teleservices ........................................... 56

Teleservices Post-COVID-19 ............................................................... 57

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature, the Governor, and Executive

Branch Agencies ........................................................................... 58

7. List of Acronyms .............................................................................. 60

Appendix A. Statewide Health Coordinating Council Roster ................. 62

8. References ...................................................................................... 64

4

1. Executive Summary

By November 1 of even-numbered years, the Statewide Health Coordinating Council

(SHCC) directs and approves the development of the Texas State Health Plan or its

updates for submission to the Governor. This plan, following the legislatively

determined purpose of the SHCC,

a

seeks to ensure that the state of Texas

implements appropriate health-planning activities and that health care services are

provided in a cost-effective manner throughout the state.

This State Health Plan focuses on how different factors affect health equity in the

state of Texas. The plan contains four sections that examine which groups are more

likely to have poorer access to care. The sections look at the challenges faced by

individuals residing in rural areas of the state, mental and behavioral health and the

ability of the state’s behavioral health care workforce to address these issues, and

finally, the role that teleservices can play in addressing health disparities.

Additionally, each section considers how COVID-19 has impacted health care in

Texas.

Based on the evidence contained within each chapter, the SHCC makes policy

recommendations consistent with goals of improving health care services in the

state and ensuring those services are cost-effective for Texans. These

recommendations include:

● Access to Care:

The state should support efforts to increase enrollment in Medicaid among

those that are eligible.

The state should examine the varied causes that limit access to care for

Texans.

● Rural Health:

The state should support new and innovative ways to bring health care

providers to rural areas.

The state should support new and innovative methods of hospital

financing.

a

See Texas Health and Safety Code Chapter 104 and Chapter 105.

5

● Mental Health and Behavioral Health Care Workforce:

The state should support efforts by schools to increase access to mental

health services for students.

The state should continue to support the work of the Texas Child Mental

Health Care Consortium.

The state should support efforts to increase the funding and stipends

available to students of the mental health professions as they complete

their education and training, as well as support the expansion of the Loan

Repayment Program for Mental Health Professionals.

● Teleservices and Technology:

The state should support new and innovative ways to get teleservices to

rural communities.

The state should encourage state, federal, and private health insurance

organizations to promote their teleservice benefits.

6

2. Background

With an eye toward improving access and health care delivery systems throughout

Texas, the 2023-2028 Texas State Health Plan provides guidance on how to achieve

a high-quality, efficient health system that serves the needs of all Texans.

Specifically, the plan identifies challenges in ensuring that a population as large and

diverse as Texas’ has access to the health care system, that health care services

are provided in an efficient and orderly manner, and that an ample health care

workforce exists to provide these services.

The plan is divided into four sections, each examining health challenges faced by

Texas and its health care workforce and proposing solutions to these challenges.

The first section focuses on issues related to differences in access to care for

individuals across the state. The second section places focus on unique health care

issues faced by those who live in rural Texas. The third section examines mental

health and behavioral health issues as well as ways to bolster the health care

workers in this field. The final section examines the impact of teleservices and

technology on the health care field, as well as how teleservices and technology may

aid in improving access to care.

7

3. Access to Care

This section discusses the health outcomes, health disparities, and demographic

differences among the Texas population. Additionally, the unique challenges faced

due to COVID-19 are discussed.

Defining Access to Care

Throughout much of Texas and the nation, access to health care is restricted by the

availability of providers, resulting in federal designations of health professional

shortage areas (HPSAs). This definition of access relies on the idea that those who

need health care can access the system if there is an adequate supply of services,

measured by the number of physicians, hospital beds, or some other metric.

1

Yet

these geographic designations do not fully reflect the multifaceted concept of

access to care. The Institute of Medicine has proposed the definition of access as

“timely use of personal health care services to achieve the best possible

outcomes”.

2

In addition to the availability of providers, this definition adds

components of timeliness and quality, the latter in the form of positive outcomes.

Another proposed definition of access is “fair access to consistently high quality,

prompt and accessible services right across the country”,

1

introducing the important

consideration of equity. This consideration is important given estimates that 30

percent of direct medical expenditures can be attributed to health disparities that

create a sicker population and that these disparities are associated with barriers to

accessing care.

3

The successful performance of health care systems at local, state, and national

levels is shown through the ability of individuals to access care when needed.

4

Simplistically, access may be considered the ease with which consumers and

communities are able to use appropriate services in proportion to their needs.

Access can then be considered in economic or other terms, such as the time

required to utilize health care services, travel distance to services, familiarity with

the health system and providers, and other considerations.

1,2,4

Researchers

4,5

have

proposed similar schema for categorizing potential barriers to access. Synthesized,

they are as follows:

• Affordability – Affordability refers to the ability of the patient to pay the

economic costs associated with health care. This may refer to directly

8

incurred costs or those associated with insurance coverage, including

premiums, deductibles, etc.

• Availability – Availability refers to the level of fit between the patient’s health

care needs and the ability of the system to fit these needs. For example,

availability is a measure of the nearness and capacity of clinicians and clinical

facilities.

• Acceptability – Acceptability refers to the ability of patients to interact with

the health care system in light of social, cultural, linguistic, and other norms

that may impede utilization.

• Appropriateness – Appropriateness refers to the extent to which the services

available fit the needs of the client. On the one hand, appropriateness may

refer to the patient’s level of comfort with the organization of the health

system, such as procedures necessary to garner an appointment, available

office hours, etc. On the other hand, this category may also include care

meeting the patient’s expectations with respect to elements such as

timeliness, the amount of time spent developing a diagnosis and treatment

plan, and the technical and interpersonal quality of the services rendered.

• Approachability – Finally, approachability refers to the extent to which

patients with health care needs are able to identify the appropriate services

available, are aware of how to reach them, and recognize the potential

impact on their health.

Of note, only one of the categories listed above is related to financial capacity of

the individual to pay for health care. While financial barriers to access are important

and associated with the presence of non-financial barriers, it is worthwhile to note

that of those reporting barriers to care, 66.8 percent of U.S. adults reported non-

financial barriers to care, a rate higher than those reporting financial barriers.

4

Seventy one percent of Medicaid patients and 49 percent of Medicare patients

reported non-financial barriers to accessing care.

With respect to availability, one of the main barriers to access that exists is a lack

of specialists and subspecialists in low-income and rural areas. For example, one

survey found that 91 percent of community health centers struggled to find

adequate off-site subspecialty care for their uninsured patients.

6

A major concern regarding acceptability is the extent to which patients are able to

receive information and instructions in their preferred language. Often linguistically

9

based barriers can result in the delay or even denial of services, challenges with

medication management, and the underutilization of preventive services.

7

The

National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Joint Commission on the

Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations are beginning to recognize the role that

language services play in the provision of quality health care. Clinical staff may

need training on when to request a medical interpreter, as unqualified interpreters

may lead to medical errors and poor patient understanding and adherence.

With respect to appropriateness, research

2

has noted that patients often experience

a cumulative burden of barriers and are frequently in need of multiple avenues

through which to access care. For example, offices seeking to increase

appropriateness might work to reduce wait times for appointments, alter their office

hours to reflect the needs of their clients, and offer advice by phone where

appropriate: all key components of the patient-centered medical home. Research

on community health centers, which often serve populations with low access, show

greater patient satisfaction not only with hours of operation but with overall care.

Finally, approachability relies on the patient to recognize when they are in need of

health services and to utilize these services, a term referred to as patient

activation.

8

Of note, different rural populations may require different strategies for

ensuring patient activation, and rural populations are likely to require different

strategies than metropolitan areas.

4,8

Ultimately, access to healthcare is a complex

idea that can be understood through all of the definitions provided.

Populations with Poor Access

In all, 18 percent of US adults experienced financial access barriers and 21 percent

experienced non-financial barriers.

5

Such barriers have been growing in the past

decade, resulting in decreased likelihood of adults having a usual source of care,

having recently seen a dentist, and having recently had a medical office visit.

9

Generally, poor access is higher in lower-income, non-white, and young adult

populations, in addition to individuals with at least one chronic disease.

5,10

Some of

these access challenges are related to affordability as racial and ethnic minorities

often comprise a disproportionate percent of the uninsured, despite absolute and

relative improvements in the rates of insurance coverage of Hispanics and African

Americans.

10,11

Indeed, reports show that access to care declined in all adult

populations from 2000 to 2010 with the most dramatic declines present in

uninsured populations.

9

Thus, it comes as no surprise that being uninsured is

associated with foregoing needed care because of cost, not having a usual source of

care, not receiving recommended screening activities, high-risk adults not getting

10

checkups in the past two years, and patients with diabetes not receiving

recommended diabetes care.

12

According to the Institute of Medicine

13

, uninsured pregnant women receive fewer

prenatal care services than insured pregnant women and are more likely to have

poor birth outcomes, including low birthweight and prematurity. Following

pregnancy, women need ongoing care for both physical and behavioral health

needs, including treatment for chronic conditions such as diabetes and

hypertension, as well as diagnosis and treatment for postpartum depression and

substance use disorders. Women without health insurance often lack access to

affordable contraceptives, including the most effective forms known as Long-Acting

Reversible Contraceptives, which includes intrauterine devices and implants.

Without access to contraceptives women are more likely to experience unintended

pregnancies. Further, uninsured women with breast cancer are 30–50 percent more

likely to die from cancer or cancer complications than insured women with breast

cancer. Uninsured women are 60 percent more likely to receive a diagnosis of late-

stage cervical cancer.

13

Additionally, considerably more Hispanic and multiracial families reported needing

an interpreter than white families.

11

These barriers may partially explain why lower

proportions of Hispanics, African Americans, and multiracial children receive needed

medical and dental care and why access to specialty care is worse for Hispanics and

African Americans.

Texas Populations with Poor Access

Women and Men

Women and men in Texas have unique issues that affect access to health care

services. When compared to men, women have similar rates of health insurance by

type with 62.3 percent carrying private insurance, 17.3 percent with

Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and 16.8 percent

uninsured.

14

The percentages of men who are uninsured are similar, with 18.4

percent uninsured. Texas men are less likely to have a personal doctor when

compared to women, with 28.9 percent of women and 37.6 percent of men

reporting not having at least one personal doctor or health care provider.

15

On the

other hand, women have reported higher rates of not being able to access medical

care due to costs, 17.2 percent compared to 13.0 percent of men.

When considering geographic distribution, men and women in border areas have

higher rates of uninsuredness than those in non-border areas.

16

While 24.5 percent

11

of both men and women in the state of Texas report not having health care

coverage, 37.9 percent of those living in border areas report not having coverage.

Furthermore, uninsuredness is higher for women than men in non-border areas,

with 42.0 percent of women reporting that they do not have coverage, while 33.8

percent of men reported that they do not have coverage.

Low-Income and Less Educated Populations

Health care access for low-income Texans varies based on socioeconomic position.

Over 44 percent of Texans at or below the federal poverty line (FPL) rely on

Medicaid as their primary insurance, while 23.7 percent rely on private insurance.

16

Almost 30 percent of Texans living at or below the FPL are uninsured. Use of

Medicaid is less common as socioeconomic position rises, dropping to 27.2 percent

for families whose income is at 200 percent of the FPL or below. Table 1 shows the

percent of Texans who are uninsured and the percent of Texans that do not have a

personal doctor separated by income.

Table 1. The percent of Texans that are uninsured and do not have a personal

doctor by income level

15

Annual Income Percent Uninsured

Percent that do not have a

Personal Doctor

<$25,000 52% 45.7%

$25,000-$49,999 25.6% 34.5%

$50,000-$74,999 20.9% 24.2%

b

$75,000-$99,999 16%

$100,000+ 8.7%

The percentage of Texans that are uninsured continues to drop as annual income

increases and lower income Texans are more likely not to have a personal doctor.

Insurance coverage is more likely among higher educated groups.

16

For example,

among those aged 25+ years with less than a high school education, 38.8 percent

b

24.2% of Texans with an annual income of $50,000 or more do not have a personal

doctor.

12

reported being uninsured. By comparison, 24.6 percent of high school graduates,

15.7 percent of those with some college, and 7.9 percent of college graduates

reported being uninsured. Likewise, 22.1 percent of those without a high school

degree reported having been unable to see a doctor when they needed to because

of cost.

15

For high school graduates, the percentage was 15.0 percent. For those

with some college and college graduates, the percentages were 16.3 percent and

9.8 percent respectively.

Children

Eleven percent of Texas children, 854,340 individuals, do not have health

insurance.

16

For those with health insurance coverage, 53.2 percent use private

health insurance and 37.9 percent are enrolled in Medicaid/CHIP. Children that

reside in households that earn 300 percent of the FPL or below have uninsured

rates between 12 and 17 percent while those above 300 percent of the FPL have

uninsured rates of 6 percent.

15

Adult Populations

Texans between the ages of 19 to 44 are uninsured at rates that fall between 25.1

and 30.2 percent.

16

For Texans that fall in the 45 to 54 year age group, only 20.6

percent reported having no health insurance coverage. For those 65 years of age or

older, only 1.8 percent reported no health insurance coverage. Over half of younger

Texans ages 18 to 29 do not have a personal doctor compared to 43.7 percent for

those ages 30 to 44, 24.7 percent for those 45-64, and 9.1 percent for those ages

65+. Between 16.5 and 19.1 percent of Texans aged 18 to 64 reported that they

were unable to see a physician due to costs. Only 5.3 percent of those aged 65+

were unable to see a physician due to costs.

15

Minority Groups

Hispanics in the state of Texas have significantly higher rates of being uninsured

when compared to other racial groups. The percentage of Hispanics that do not

have health insurance coverage is 27.3, compared to 10.0 percent of whites, 15.0

percent of African Americans, and 11.4 percent from other racial backgrounds.

16

White and African American Texans are more likely to have a personal doctor (75.6

percent of whites and 76.4 percent of African Americans), when compared to

Hispanics at 52.9 percent. Percentages of Hispanics and African Americans that

were unable to access a physician due to costs were similar, at 20.2 and 14.7

percent respectively, while only 11.3 percent of whites and 12.2 percent of multi-

racial or other-raced individuals were unable to see a physician due to costs.

15

13

Border Counties

c

Texans that reside near the Texas/Mexico border are less likely to have health

insurance coverage when compared to the state as a whole, 37.9 percent compared

to 24.5 percent.

16

When considering only those aged 18-64 in non-border areas of

the state, those who were uninsured was estimated to be 21.9 percent. In border

areas, this percentage was almost doubled at 38.5 percent. The border region also

has higher rates of Medicaid utilization when compared to the rest of Texas, 27.3

percent compared to 16.2 percent. Additionally, those living in border areas are less

likely to have a personal health care provider, more likely to forgo needed medical

treatment because of cost, and less likely to have had a routine checkup in the past

year.

15

COVID-19 and Access

Nationwide Access

Communities across the U.S. and specifically in Texas have been impacted by

COVID-19, with communities being impacted in different ways.

17

Due to the high

demands of COVID-19 on medical staff, many individuals have reported

experiencing reduced access.

18

This issue was particularly severe in the earlier

months of the pandemic. According to experimental survey research, in June and

July of 2020, 38.7 percent of adults reported that they were unable to receive one

or more types of care in the past two months due to the pandemic. This percentage

dropped to 28.2 percent in August 2020. In May and June 2021, it had fallen

further to 12.7 percent. According to the study, in each time period, women were

more likely than men to report that the pandemic had caused them to be unable to

receive one or more types of medical care.

18

Furthermore, the onset of COVID-19

resulted in 5.4 million lost jobs in the U.S. and for many Americans the loss of a job

also resulted in the loss of health insurance, reducing millions’ access to health

care.

19

c

Border area is defined through the La Paz Agreement of 1986 and includes 32 Texas

Border counties: Brewster, Brooks, Cameron, Crockett, Culberson, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards,

El Paso, Frio, Hidalgo, Hudspeth, Jeff Davis, Jim Hogg, Kenedy, Kinney, La Salle, Maverick,

McMullen, Pecos, Presidio, Real, Reeves, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Webb,

Willacy, Zapata, and Zavala.

14

Access in Texas

According to one study, an estimated 659,000 Texans lost health insurance as a

consequence of job-loss due to COVID. Another study suggests the number of jobs

lost may be even higher, indicating that as many as 1.6 million Texans lost their

employer-sponsored health insurance due to job-loss during the COVID-19

pandemic.

20

Such losses during the pandemic are particularly concerning because

when individuals are without health coverage they tend to delay seeking medical

attention.

19

This may have led to additional spread in the virus among those who

did not know that they were infected.

Race & Ethnicity

Additional concerns around COVID-19 relate to differences in vaccination rates

based on race. One major concern, particularly early in the vaccination distribution

process, was ensuring that communities had equal access to the vaccine.

21

As of

2022, in Texas, 53 percent of white individuals have received at least one dose of

the vaccine, while only 46 percent of African-American individuals have been

vaccinated. In contrast, 59 percent of Hispanic individuals have been vaccinated,

and 73 percent of Asian individuals have been vaccinated in Texas.

22

Nationally, 48

percent of white individuals, 32 percent of African-American individuals, 27 percent

of Hispanic individuals, and 48 percent of Asian individuals have received at least

one dose of the vaccine.

23

Texas exceeds vaccination rates among race/ethnicity

categories compared to the nation as a whole.

Strategies for Improving Access

Three broad strategies are available to address the gaps in access to care identified

above: improving rates of insurance coverage; increasing the availability of health

care professionals, facilities, and services; and a reduction in social barriers to care.

Ultimately, improving timely access to and quality of care will depend on

collaboration among local clinicians, hospital leaders, insurance companies,

policymakers, and community stakeholders.

12

Success in improving access to care

relies on concurrent efforts to reduce financial and nonfinancial access barriers.

5

Additionally, Texas has fewer physicians per capita than the national average,

creating additional hurdles for those who need access to care.

24

Increasing the

number of available physicians and other health care providers will improve access

and lessen the burden on those health care professionals in the state. A

fundamental aim of the redesign of primary care services is improving access to

care. Patients who reported having a usual site of care and a provider at that site

15

are more likely to access that care, receive preventive services, and have improved

health.

2

The following strategies seek to improve access by making health care

more affordable, available, acceptable, appropriate, and approachable.

Covering More Texans

In order to improve the affordability of care and thus access in Texas, it should be a

priority of this state to increase the number of Texans with insurance coverage and

a usual source of care. This can be accomplished through greater public coverage of

the poor and improved access to physicians and other providers within the public

system. Projections

25

demonstrated that low-income Medicaid enrollees were

significantly more likely to have a usual source of care and less likely to have

unmet health care needs. Publicly covered adults are also more likely to report

timely care and less likely to delay or go without needed medical care because of

costs.

With respect to mothers and their children, increasing the percentage of covered

mothers is likely to have a significant effect on access to health care, ability to pay

medical bills, and mental health. Children are also expected to benefit, since their

coverage and access to care have been shown to improve when their parents have

coverage. Increasing the number of mothers with insurance may also improve

outcomes for children in other ways, such as by reducing maternal depression,

which can affect parenting abilities.

Medicaid, along with its companion CHIP, is a state/federal partnership that

provides health care coverage to low-income children and their caretakers,

pregnant women, people age 65+, and people with disabilities. Some states,

though not Texas, have chosen to extend Medicaid coverage to childless,

nondisabled, working age adults.

In Texas, the Medicaid and CHIP programs cover over four million people.

26

A large

body of evidence suggests that these individuals are more likely to have a usual

source of care, more likely to receive preventive health services, and less likely to

have unmet or delayed needs for medical care than if they were uninsured.

25

Research has consistently indicated that people with Medicaid coverage fare much

better than their uninsured counterparts on measures of access to care, utilization,

and unmet needs. Evidence further shows that, compared to low-income uninsured

children, children enrolled in Medicaid are significantly more likely to have a usual

source of care and to receive well-child visits and immunizations, and significantly

less likely to have unmet or delayed needs for medical care, dental care, and

prescription drugs due to costs. Moreover, in some states that expanded Medicaid,

16

reports note that the expansion led to improvements in prenatal care use, in terms

of either earlier or more adequate prenatal care.

The federal government currently subsidizes, via tax credit, marketplace health

insurance premiums for households that earn from 100 percent to 400 percent of

the FPL.

13

Texas adults earning below the FPL, but who do not qualify for Medicaid

or for federal subsidies to purchase care on the insurance exchange, fall into what

is known as the “coverage gap.” Nationally, over two million poor uninsured adults

fall into the coverage gap, a third of which reside in Texas. In total, there are

771,000 people that fall into the coverage gap in Texas, leaving them with no

realistic options for affordable health insurance coverage.

Provider Participation in Medicaid

In order to improve access to care in Texas, it is important to address shortages in

providers treating low-income individuals. Among the challenges providers face are

the administrative burden of participation in Medicaid, the complexity of many

patients’ needs, challenges in arranging mental health and specialty referrals, large

patient panels associated with a general shortage of physicians, and lower

reimbursement rates than other payers. National research has indicated that

physicians may be optimistic about the ability of electronic health records and

medical homes to mitigate challenges.

27

With respect to reimbursement, Texas is one of 22 states that pays 75 percent or

less for Medicaid physician fees when compared to Medicare physician fees.

5

There

are 24 states that pay physician fees at 75 percent to 100 percent and three that

pay greater than 100 percent for services under state-run Medicaid programs when

compared to Medicare. Texas Medicaid pays approximately 65 percent compared to

the federally funded Medicare program.

3

Due to the gap in physician reimbursement

between the two programs, physician participation has diminished. The number of

Texas physicians willing to accept new Medicaid patients fell from 67 percent in

2000 to 31 percent in 2012

4

and increased slightly to 34 percent in 2015.

1,3

In

order to guarantee strong provider networks for Texas low-income residents, Texas

should strive to pursue a comprehensive approach to improving provider experience

and increasing participation in Medicaid.

From 2013 to 2014, the federal government provided additional funding that

allowed states to increase Medicaid payments to primary care physicians to match

payments for the same services through Medicare.

28

These funds successfully

sought to increase participation in Medicaid programs, especially primary care

17

services, effecting a five percent rise in physician participation in Medicaid during

this time.

1,3

However, the increase in payments was not made permanent in Texas.

Other Policy Considerations

Generally, the racial and ethnic profile of health care providers in Texas does not

reflect that of the population at-large. In addition to cultural preferences pondered

in the mental health section of this report, it has been shown that minority

physicians are significantly more likely to care for minorities, the publicly insured,

and uninsured patients.

11

Likewise, a more diverse workforce may help address the

need for linguistic competency within the health provider workforce. In the interim

though, the standardization of payment mechanisms for interpreter services and

their inclusion in health plans may improve access for those who are not proficient

in English.

7

The expansion of teleservices, the appropriate utilization of physician assistants and

advanced practice registered nurses, and stronger financial incentives for clinicians

to practice in underserved areas may be useful for expanding access in

geographically underserved areas.

5

Policy Developments

The Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) pool in the Texas

Healthcare Transformation and Quality Improvement Program Medicaid 1115

Demonstration (Waiver) began in 2012 and was set to conclude in September

2021.

29

The DSRIP program benefitted Texans and the Texas health care delivery

system. Texas providers earned over $15 billion in DSRIP funds from 2012 to

January 2019, and it served 11.7 million people and provided 29.4 million

encounters from October 1, 2013 to September 30, 2017. As the DSRIP pool came

to a close, the state of Texas began working on new programs to support services

in Texas. As part of the DSRIP transition plan, several programs that offer access to

care, often for underserved communities, have been introduced. The Health and

Human Services Commission (HHSC) submitted the following programs, which have

been approved:

● Texas Incentives for Physician and Professional Service (TIPPS)

30

: A value-

based directed payment program for certain physician groups providing

health care services to children and adults enrolled in the STAR, STAR+PLUS

18

and STAR Kids Medicaid programs.

d

Eligible physician groups include health-

related institutions, indirect medical education physician groups affiliated

with hospitals, and other physician groups.

● Comprehensive Hospital Increased Reimbursement Programs

31

: A directed

payment program for hospitals providing health care services to adults and

children enrolled in STAR and STAR+PLUS. Eligible hospitals include

children's hospitals, rural hospitals, mental health hospitals, state-owned

hospitals, and urban hospitals.

● Directed Payment Program for Behavioral Health Services

32

: A directed

payment program for community mental health centers to promote and

improve access to behavioral health services, care coordination, and

successful care transitions. It also incentivizes continuation of care for STAR,

STAR+PLUS, and STAR Kids members using the Certified Community

Behavioral Health Clinic model of care.

● Rural Access to Primary and Preventive Services

33

: A directed payment

program for rural health clinics that provide primary and preventative care

services to STAR, STAR+PLUS, and STAR Kids members.

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature,

the Governor, and Executive Branch Agencies

Encourage the use of health care teams that include different types of

health care providers.

In 2021, 34 of the 254 counties in Texas had no primary care physicians and 31

counties had no direct patient care physicians.

24

Using teams that include different

types of health care providers can facilitate the provision of care for those without

physicians nearby. Using teams also promotes more efficient care in addressing the

health care needs of patients and provides physicians with the opportunity to focus

on the more serious and complex needs of patients. This shift would help to

redistribute responsibilities and allow physicians to utilize their time working with

those patients who need their expertise. This would allow physicians to more

efficiently allocate their time, which is critical due to the shortage of physicians in

the state.

d

STAR, STAR+PLUS, and STAR Kids are Texas Medicaid and CHIP Programs. More

information about the individual programs can be found at

https://www.hhs.texas.gov/services/health/medicaid-chip/medicaid-chip-members

.

19

Conduct a study examining which factors decrease physician participation

in Medicaid programs.

Improving our understanding regarding why more physicians do not participate in

Medicaid is an important first step in increasing access. Many factors may influence

physicians’ decision to not participate in Medicaid programs, such as the process of

becoming a Medicaid provider, patient participation, reimbursement rates, etc.

Understanding the hurdles preventing physicians from participating will allow for

more targeted approaches in improving physician participation in Medicaid which

would improve access for many Texans.

Support the furthering of health literacy and utilization of preventative

services for those on Medicaid.

According to the CDC, health literacy is “the degree to which individuals have the

ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-

related decisions and actions for themselves and others.”

34

Furthering health

literacy would aid in improving health outcomes.

35

Research has shown that

patients who are better informed make better choices for their health, ultimately

improving health outcomes. Health literacy is also key for effective preventative

medicine.

36

Health literacy helps prevent health problems, protect individuals’

health, helps people better manage health problems when they arise, and improves

individuals’ ability to identify health problems early, which is often key to

treatment.

37

Additionally, preventative medicine improves health outcomes, and

increasing the utilization of such services would improve the health of Texans.

38

During the 87

th

Legislature, Regular Session, the House Select Committee on Health

Care Reform was created. The committee’s duties are to “examine the potential

impact of delayed care on the state’s health care delivery system, health care costs,

and patient health outcomes, as well as best practices for getting patients with

foregone or delayed health interventions back into the health care system. The

study should consider patient delays in obtaining preventative and primary health

services…” Together, improving health literacy and utilization of preventative

services for those on Medicaid could improve the health of Texans across the state.

Support efforts to increase enrollment in Medicaid among those that are

eligible.

During the 87

th

Legislature, Regular Session, the House Select Committee on Health

Care Reform was created. The committee is charged with studying ways to improve

20

outreach to families with children who are eligible for, but are not enrolled in,

Medicaid or CHIP. This targets increasing enrollment of children who are eligible,

but there should also be similar efforts to increase outreach for all those who are

eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled in the program.

Continue to support programs like TIPPS, which provides increased

Medicaid payments to certain physician groups providing health care

services to persons enrolled in STAR, STAR+PLUS, and STAR Kids.

On March 25

th

, 2022 the TIPPS program was approved by the Centers for Medicare

and Medicaid Services.

32

This program is for delivery system and provider payment

initiatives under Medicaid managed care plan contracts. Three classes of providers

are eligible to participate: (1) health-related institution physician groups, (2)

physician groups affiliated with hospitals that receive indirect medical education

funding, and (3) other physician groups.

TIPPS funds are paid through three components of the managed care capitation

rates:

• Component 1 is equal to 65 percent of the total program value and provides

a uniform dollar increase paid monthly. Only health-related institutions and

indirect medical education physician groups are eligible for Component 1.

• Component 2 is equal to 25 percent of the total program value and provides

a uniform rate increase paid semi-annually. Only health-related institutions

and indirect medical education physician groups are eligible for Component 2.

• Component 3 is equal to 10 percent of the total program value and provides

a uniform rate increase for applicable outpatient services and is paid at the

time of claim adjudication. All participating physician groups are eligible for

Component 3.

Increased Medicaid payments compensate providers and may encourage greater

participation in the programs, which would increase the capacity to provide care to

those on Medicaid.

Support the development of quality thresholds that must be met by those

providers participating in TIPPS.

The TIPPS program has the following quality goals:

21

• Promote optimal health for Texans at every stage of life through prevention

and by engaging individuals, families, communities, and the health care

system to address root causes of poor health.

• Promote effective practices for people with chronic, complex, and serious

conditions to improve people’s quality of life and independence, reduce

mortality rates, and better manage the leading drivers of health care costs.

Subsequently, TIPPS providers must provide qualitative and numeric data, which

will be used to monitor provider-level progress toward state quality objectives.

While these quality measures must be reported, there are no minimums that

currently must be met so there should be a shift to developing standards that would

assess whether care is meeting or exceeding the quality goals that have been

developed.

Examine the varied causes that limit access to care for Texans.

While affordability plays a role in access to care, it is only one factor to consider

when examining barriers to health care. Lawmakers should further examine other

factors that limit access to care. This includes the level of fit between patients’

health care needs and the ability of the system to fit these needs, which includes

the nearness and capacity of clinicians and clinical facilities.

5

Another factor that

should be examined is the ability of patients to interact with the health care system

in light of social, cultural, linguistic, and other norms that may impede utilization.

These factors are particularly important due to the large Hispanic population in the

state. Texas had a higher percentage of individuals five years of age and over who

spoke a language other than English at home (35.5 percent) compared to the

nation (21.5 percent) from 2014 to 2018.

39

Texas has the second highest

percentage of individuals who spoke a language other than English at home (behind

California). The most common language other than English spoken at home in

Texas was Spanish (29.5 percent), followed by Asian and Pacific Islander languages

(2.9 percent) and other Indo-European languages (2.2 percent).

Additionally, the extent to which the services available fit the needs of the patient

should also be examined.

5

This may include the patient’s level of comfort with the

organization of the health system. It may also include care meeting the patient’s

expectations with respect to elements such as timeliness, the amount of time spent

developing a diagnosis and treatment plan, and the technical and interpersonal

quality of the services rendered. Finally, the extent to which people with health care

needs are able to identify the appropriate services available, are aware of how to

22

reach them, and recognize the potential impact on their health should be included

when examining access to care.

23

4. Rural Health

This section discusses the health outcomes, health disparities, and demographic

differences in rural areas throughout the state of Texas. Additionally, the unique

challenges faced by hospitals and health practices are discussed.

Health Outcomes in Rural Areas

Nationally, residents in rural areas have a life expectancy 1 to 5 years less than

residents in urban areas.

40

Those in rural areas are more likely to smoke, less likely

to exercise, and have less nutritional diets than those in suburban areas.

41

These

factors contribute to higher mortality rates and higher rates of chronic diseases in

rural areas. Approximately 43 percent of deaths in rural areas can be attributed to

modifiable risk factors such as smoking, excessive drinking, and obesity, compared

to about 37 percent in urban areas.

42

Rural residents are more likely to have

hypertension, diabetes, arthritis, and high cholesterol than urban residents. Rural

children are more likely to be obese than urban children.

43

Rural areas also have

higher age-adjusted mortality for heart disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease,

and stroke.

44

In 2019, the age-adjusted mortality was 834.0 per 100,000

population in rural communities and 693.4 in urban communities.

45

Rural residents

were also more likely to die due to unintentional injury, drug poisoning, and suicide

than urban residents.

Rural health in Texas faces both similar and unique challenges compared to rural

health nationally.

46

The rural populations of Texas are incredibly diverse; for

example, the Texas-Mexico border area is predominantly Hispanic (88.4 percent)

compared with the rest of the state (35.5 percent).

47

There are colonias, which are

“residential area[s] lacking some basic infrastructure like a drinking water supply,

sewage treatment, paved roads, adequate drainage, etc.”

48

Adult residents of

colonias report worse physical health compared to adults nationally and Hispanic

adults as a whole.

49

COVID-19

The first pandemic surge in Spring 2020 resulted in higher incidence and mortality

in urban areas. During the second surge in Summer 2020, the rates in rural areas

surpassed those in urban areas. Since then, incidence and mortality rates have

remained higher in rural than urban areas.

50

Rural areas felt a greater impact from

COVID-19 due to poor health literacy and health care infrastructure, as well as

24

having higher proportions of elderly and people with comorbidities.

51

Rural areas

have higher incidences of underlying medical conditions that increase the risk of

severe illness from COVID-19, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and

smoking.

52

Rural areas also tend to have lower COVID-19 vaccination rates.

53

Residents of rural areas are more likely to distrust vaccines than those of urban

areas.

54

Emergency Medical Services

Emergency medical services (EMS) face challenges in rural Texas.

55

As

requirements for EMS personnel increase and access to training in rural Texas

decreases, this exacerbates staffing issues in rural Texas. Rural EMS providers tend

to be staffed less than urban EMS. EMS agencies are often staffed by volunteers or

a mix of volunteers and paid staff. One study found that those agencies staffed by

volunteers are often less trained and would benefit from additional training for their

positions.

56

Additionally, a study found that rural EMS are more likely to lose staff

to burnout than urban EMS. The closure of rural hospitals also puts strain on EMS

by increasing drive times to facilities.

57

The Texas Department of Transportation

Safety Division through the Texas A&M Engineering Extension Service provides

funding for Texas Rural/Frontier EMS training; however, funds are limited.

55

Senate

Bill 8 of the 87

th

Legislative Session, 3

rd

Special Session, allocated funding for EMS

education programs.

58

This included $21 million that goes towards scholarships for

EMS students with special consideration for those in rural parts of Texas.

59

Teleservices

The current COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the rapid expansion of telehealth

and telemedicine services. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has

expanded the number of services eligible for telehealth.

60

Additionally, emergency

rules were issued expanding telehealth and telemedicine.

61

A report identified

telemedicine as a way for rural residents to access subspecialist services and for

expanding services offered by nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

62

Broadband access is a barrier to receiving telehealth and telemedicine in rural areas

of Texas.

55

There are over 2 million households in Texas without high-speed

internet access.

63

Fiber infrastructure and broadband access have been identified as

a key concern among rural residents.

55

Older Adults in Rural Areas

Nationally, the rural population is older than the urban population.

64

In 2015, the

median age was 51 years in rural areas and 45 in urban areas. Rural communities

25

also had a higher proportion of people aged 65 and older in 2016, as this age group

comprised 18.4 percent of the population in rural areas compared to 14.5 percent

in urban areas. According to the Texas Demographic Center, rural counties

experienced the greatest increases in median age from 2010 to 2018.

65

For

instance, 18 percent of rural counties saw an age increase of two to four years, and

16 percent saw an increase of more than four years. Metropolitan counties saw an

age increase of two to four years in 13 percent of counties and more than four

years in only 2 percent of counties. Older adults are at higher risk of chronic

disease, and many manage two or more chronic conditions.

66

Older adults often

require more complex health care that may be more difficult to receive in rural

areas.

Challenges for Low-Income and Uninsured Populations in

Rural Areas

In 2018, Texas had the highest number of uninsured people in any state.

67

Rural

households also report a lower median income than urban households.

64

In 2016,

the median income was $46,000 for rural households and $62,000 for urban

households. Moreover, the poverty rate was 16.9 percent in rural areas and 13.6

percent in urban areas. In 2013, the food insecurity rate was 15.8 percent in rural

communities and 14.5 percent in urban communities. Low-income communities

have limited access to fresh foods and environments that are conducive to physical

activity.

68

Income and poverty have been established as being associated with poor

health and increased mortality.

In summation, people that live in rural areas tend to have poorer health outcomes

when compared to their urban counterparts. These issues are highlighted by the

lower incomes and lower insurance rates in rural areas. These issues make rural

health access complex and highlight why the issues surrounding facilities and

providers, as discussed below, are particularly important.

Hospital and Nursing Facility Closures

Access to quality health services was identified as the top priority in rural health

over the last decade.

46

Types of access that were identified as the most concerning

include emergency services, primary care, and insurance. Since 2010, 26 rural

hospitals have closed in Texas.

69

Hospital closures in rural areas negatively impact

access to care and potentially health outcomes as well.

70

Hospital closures lead to

loss of access to emergency care, making emergency medical transport even more

important. For patients that rely on hospitals for specialty care or referrals, they

26

lose that access as well. In particular, communities often lose access to obstetric

care, mental health care, and diagnostic testing when hospitals close. Communities

that lose hospitals have a difficult time recruiting employers and industries to the

area.

Hospital closures can lead to increases in the amount of time patients must travel

to obtain care.

71

Longer travel times can lead to negative health outcomes,

especially for conditions like traumatic injuries and stroke.

There was a significant amount of nursing home closures between June 2015 and

June 2019.

72

Research shows there were 555 nursing home closures nationwide

during these years, including 65 in Texas. Moreover, 40 percent of the nursing

home closures in Texas were in rural areas.

In 2018, Texas had the highest number of uninsured people in any state, and Texas

has not expanded Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

67,73

People of

color are more likely to be low-income and uninsured, so Medicaid expansion

affects them more significantly.

75

Additionally, the ACA expansion of Medicaid has

been found to be associated with reduced probabilities of hospital closures.

76

In

states that expanded Medicaid, rural hospitals increased revenue that likely reduced

the number of closures.

Providers

Data from the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) indicate that

non-metropolitan counties had 36.7 percent fewer primary care physicians per

capita than metropolitan counties in 2021.

24

Non-metropolitan counties had 56.6

percent fewer direct patient care physicians per capita than metropolitan counties.

In the same year, there were 34 counties in Texas with no primary care physicians

and 31 counties with no direct patient care physicians.

Some reasons why health care clinics close include physician retirement or because

they, like hospitals, are not financially solvent. Clinic closures in rural Texas can

lead to longer drives to access care and delaying care due to the distance.

77

An

example was highlighted in a news article that described the impact of the closure

of the clinic in Cottle County that resulted in one resident having to drive 30

minutes to Childress County, the next closest clinic. Residents in rural areas must

make hard choices about whether or not to move to obtain better access to care,

especially as they age.

27

Older Providers

As illustrated by data from DSHS, direct patient care physicians in rural Texas areas

tend to be older.

24

In 2021, the median age of direct patient care physicians was 49

years in metropolitan counties and 56 years in non-metropolitan counties.

As physicians in rural areas age and retire, they may leave practices that have to

close because there are no physicians in the area to continue the practice.

78

When

the nurse practitioner who ran the only health clinic in Memphis, Texas retired, the

clinic closed. Now residents must drive approximately 140 miles to receive care.

Obstetric Services

According to DSHS data, non-metropolitan counties had 63.4 percent fewer

obstetricians and gynecologists per capita than metropolitan counties in 2021.

24

Projections show that the shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists is projected to

continue through 2032 in seven of the eight public health regions in Texas.

79

Nationally, the number of hospitals providing obstetric care in rural areas has

decreased over the last 20 years.

80

This can lead to increased travel time for

women in rural areas. A study that examined factors associated with rural obstetric

unit closures found that common risk factors included: low number of births,

private hospital ownership, low number of family physicians in county, and lower

income county.

As obstetric units close, women must drive farther distances to give birth.

80

This

may be dangerous for women with high-risk pregnancies or complications. Obstetric

unit closures in rural counties that are not adjacent to urban counties are

associated with higher rates of preterm births.

81

Policy Recommendations for the Legislature,

the Governor, and Executive Branch Agencies

Support new and innovative methods of hospital financing.

Hospital financing is a significant factor in whether a hospital stays in a rural area.

By encouraging innovative financing, Texas can create novel solutions to strengthen

rural hospitals. In the report from Texas A&M University, facility conversion is

identified as a solution for hospitals.

62

Another model, the Pennsylvania Rural

Health Model, transitions rural hospitals from fee-for-service to global budget

28

payments.

82

The Texas A&M University Rural and Community Health Institute

provides technical assistance to rural hospitals in such areas as finance challenges,

grant writing, and community engagement.

83

By evaluating services, hospitals can best adjust their services to meet the needs of

the community. Additionally, facilities can formalize relationships with other

facilities to provide other services. Sharing resources such as key personnel, health

information technology, and board membership can help to optimize limited fiscal

resources and improve continuity of care.

84

Monitor the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the number of

uninsured people in Texas.

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, Texas had the highest number of uninsured

people of any state. More than 4.9 million people in Texas, or about 17.3 percent of

the state’s population, were uninsured in 2020.

85

An estimated 659,000 adults in

Texas lost coverage due to job loss during the pandemic.

86

As this is a rapidly

changing situation, leaders must continue to track and determine the impact of the

pandemic on the number of uninsured people in the state.

Monitor the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the shortage and

maldistribution of health care providers.

A survey conducted by the American Association of Critical Care Nurses found that

92 percent of respondents felt that the pandemic had “depleted nurses at their

hospitals and, as a result, their careers will be shorter than they intended.”

87

Many

physicians are also experiencing burnout due to the pandemic.

88

Nationally,

employment in the health care field is down by 306,000, or 1.9 percent, since

February 2020.

89

This could exacerbate the existing workforce maldistribution in the

state and shortage in rural areas. Notably, the number of Texas counties

designated as primary care shortages areas jumped from 129 in 2019 to 228 in

2021.

90

During the pandemic, many nurses left their jobs to become traveling nurses due to

higher earning potential. The nursing shortage has driven up the price of traveling

nurses, making employing them much more costly to hospitals that are

experiencing staffing shortages.

91

To adequately provide for the medical needs of all

Texans, the state must correct its chronic shortage and maldistribution of health

care providers.

29

Support expanding the state’s loan repayment programs to include more

health professions.

The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board has loan repayment programs for

physicians, nurses, and mental health professionals who practice in underserved

areas.

92

Two of these are the State Physician Education Loan Repayment and Rural

Resident Physician Grant programs. Research by the Association of American

Medical Colleges shows that physicians tend to stay and practice medicine in the

area where they trained.

93

The 2016 National Health Service Corps Participant

Satisfaction Survey found that 88 percent of participating clinicians who received

loan repayment assistance in exchange for working in underserved areas stayed in

that area for up to one year after their obligation, and 43 percent intended to stay

for five or more years.

94

Expanding the loan repayment programs to include more

health professions could increase the number of people practicing other health

professions in underserved areas and incentivize people to enter a health

profession. These programs should also be advertised to expand their reach.

Support new and innovative ways to bring health care providers to rural

areas.

Rural Americans live an average of 10.5 miles from the nearest hospital, compared

to 4.4 miles for those in urban areas.

95

By supporting alternative methods of

bringing health care providers into rural areas, more patients in underserved areas

could receive care. Programs like Care Van, a collaboration between the Caring

Foundation of Texas and other institutions including the Texas Tech University

Health Sciences Center, brings health care providers to communities, including rural

communities, at no cost to those who qualify.

96

The availability of teleservices must also expand to ensure greater access to health

care services. There are currently numerous barriers to the practice of telehealth

and telemedicine. House Bill 5, 87

th

Legislature, Regular Session, 2021, established

a Broadband Development office to improve access to broadband services in rural

areas.

97

A Texas A&M University report identified telemedicine as a way for rural

residents to access subspecialist services and for expanding services offered by

nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

62

Ensure that high school students are educated about the health care

system and careers in health care.

Health care workers from rural areas are more likely to practice in rural areas.

Therefore, high school students in rural areas should be encouraged to enter the

30

health care field.

98

They can be provided with education about how the health care

system works, what careers are available to them in health care, what kind of

preparation is necessary for these careers, and how to apply to training and

educational programs. The Health Professions Recruitment and Exposure at the

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center accomplishes these goals by

“expos[ing] high school students to medicine and science through a variety of

workshops and hands-on activities.”

99

High schoolers can also begin their path toward professional licensure. Seven

vocational nursing programs in Texas offer options for high school students to take

nursing courses and become licensed shortly after high school graduation.

100

Supporting programs for high school students could increase prospective entrants

into health care fields experiencing workforce shortages.

31

5. Mental Health and Behavioral Health

Workforce

This section covers the growing need for U.S. and Texas mental health services for

distinct demographic categories. In addition, it discusses and displays the shortages

of the behavioral health workforce and the challenges faced for recruitment and

retention.

Background

Nationally, almost half of adults (46.4 percent) will experience a diagnosable

mental disorder in their lifetime.

101

On an annual basis, over one in four adults

(26.2 percent) in the U.S. experience mental illness and about one in 17 (5.8

percent) experience a serious mental illness.

102

Half of diagnosable mental disorders

begin by the age of 14 and three-fourths begin by the age of 24.

101

Moreover, an

estimated 14 to 20 percent of young people annually have mental, emotional, and

behavioral disorders.

103

According to the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 52.9 million adults

aged 18+ (21.0 percent) experienced mental illness and 14.2 million adults (5.6

percent) experienced serious mental illness in the past year.

104

Among children and

adolescents aged 12 to 17, 4.1 million (17.0 percent) experienced a major

depressive episode and 2.9 million (12.0 percent) experienced a major depressive

episode with severe impairment in the past year.

The 2020 survey results also indicate that only 46.2 percent of adults who

experienced mental illness and 64.5 percent of adults who experienced serious

mental illness in the U.S. received inpatient or outpatient mental health services or

took prescription medication for a mental health condition in the past year.

Furthermore, an unmet need for mental health services in the past year was

perceived by 30.5 percent of adults who experienced mental illness and 49.7

percent of adults who experienced serious mental illness. Among children and

adolescents aged 12 to 17 who experienced a major depressive episode, just 41.6

percent received treatment for depression in the past year.

Additionally, the 2020 survey results indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic

negatively affected mental health. From October to December 2020, the majority of

adults (73.0 percent) and the majority of children and adolescents aged 12 to 17

32

(69.1 percent) in the U.S. perceived that the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative

effect on their mental health. For adults as well as children and adolescents aged

12 to 17, 18.3 percent perceived that their mental health was negatively affected

“quite a bit or a lot” because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Another 54.7 percent of

adults and 50.8 percent of children and adolescents perceived that their mental

health was negatively affected “a little or some” because of the COVID-19

pandemic.

A national study conducted by the Center for Studying Health System Change found

that 66.8 percent of primary care physicians were unable to refer their patients to

high-quality outpatient mental health services.

105

This percentage of unavailability

is much higher than the percentages reported by primary care physicians for other

common referrals, including high-quality specialist referrals (33.8 percent), high-

quality imaging services (29.8 percent), and nonemergency hospital admissions

(16.8 percent). Primary care physicians reported that the unavailability of high-

quality outpatient mental health services was due to lack of or inadequate health

insurance coverage, a shortage of providers, and health plan barriers.

Despite the established need for mental health services, a mental health workforce

shortage is evident nationwide. According to the Health Resources and Services

Administration (HRSA), over 148.2 million people in the U.S. live in the 6,222

HPSA’s for mental health.

106

Areas designated by HRSA as HPSA’s for mental health

may be based on the ratio of population to psychiatrist, the ratio of population to

core mental health provider (includes psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, clinical

social workers, psychiatric nurse specialists, and marriage and family therapists), or

both of these ratios.

● If based on the ratio of population to psychiatrist, geographic designations

must have a ratio of 30,000 to 1. In areas with high needs,

e

geographic

designations or population designations must have a ratio of 20,000 to 1.

● If based on the ratio of population to core mental health provider, geographic

designations must have a ratio of 9,000 to 1. In areas with high needs,

geographic designations or population designations must have a ratio of

6,000 to 1.

e

High needs areas are those that meet specific qualifications on population to provider

ratios, percent of population below the FPL, and/or distance to health care. More

information can be found at

Scoring Shortage Designations | Bureau of Health Workforce

(hrsa.gov).

33

● If based on the ratios of both population to psychiatrist and population to

core mental health provider, geographic designations must have a population

to psychiatrist ratio of 20,000 to 1 and a population to core mental health

provider ratio of 6,000 to 1. In areas with high needs, geographic

designations or population designations must have a population to

psychiatrist ratio of 15,000 to 1 and a population to core mental health

provider ratio of 4,500 to 1.

Most HPSA’s for mental health are designated based on the ratio of population to

psychiatrist. Estimates show that an additional 7,420 mental health providers would

be needed to remove the existing health professional shortage area designations

for mental health in the U.S.

Demand for mental health services is projected to increase nationwide due to the

aging population.

107

The number of older adults with mental and behavioral health

problems is projected to increase by 11 million from 1970 to 2030. Moreover, the

aging of the national population requires behavioral health service providers with

special knowledge and skills.

108

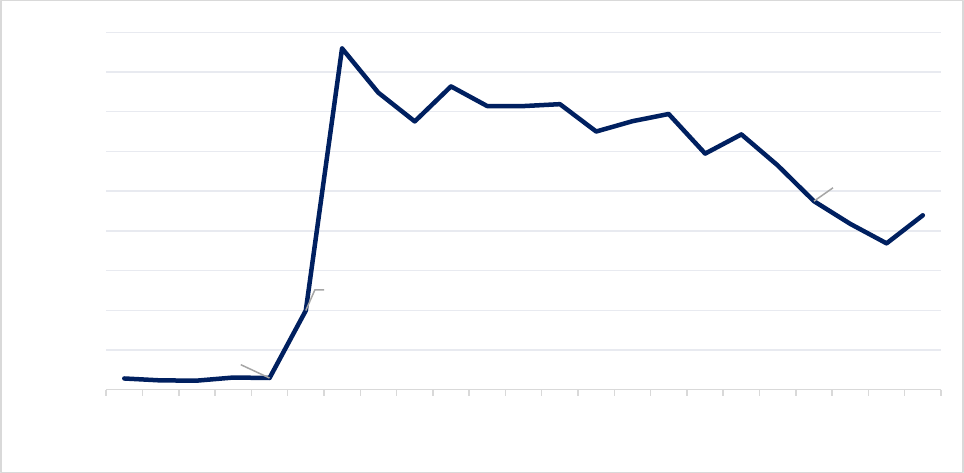

HRSA issued national-level supply and demand projections for several behavioral

health occupations from 2016 to 2030 that incorporate estimates of unmet need for

behavioral health services. These projections are based on the unlikely assumption

that there are no changes in the levels of behavioral health care service provision or

utilization from 2017 to 2030. Based on these projections, there will be an

estimated shortage of 34,940 addiction counselors,

109

21,150 adult psychiatrists,

14,300 clinical, counseling, and school psychologists, and 40,140 mental health

counselors nationwide in 2030. These projections also indicate that there will be an

estimated surplus of 3,720 child and adolescent psychiatrists, 1,650 marriage and

family therapists, 2,440 psychiatric nurse practitioners, 1,500 school counselors,

and 200,280 social workers nationwide in 2030.

Workforce-based explanations for an inadequate supply of mental health and

addiction providers at-large generally focus on insufficient numbers of providers,

high turnover, low compensation, a lack of diversity, and limited competency in

evidence-based treatments.

108

Describing the mental health workforce shortage

quantitatively can be problematic, as relevant data have not been universally

collected and there is no agreed-upon definition of adequate supply.

110

However,

efforts to describe the mental health workforce shortage should consider both the

population’s need for mental health services and the number of providers available

to deliver these services.

34

Texas’ Need for Mental Health Services

As noted above, one part of describing a workforce shortage involves

demonstrating the needs of the population for mental health services. A standard

definition of mental health need is not available at the state or national level.

Children

No reliable statewide survey data on mental health needs exist for children younger

than high school age. However, data from HHSC indicate that 44,031 children who

were 13 years of age or younger received mental health services from local mental